Canada has a strong, globally competitive financial sector that has proven to be stable, resilient and well respected. However, compared to other developed countries, Canada has experienced delays in rolling out frameworks, including legislation, that enable the fintech ecosystem to evolve in a way that is reliable and safe for end users, while still allowing them to leverage the power of technology.

Fortunately, several key government and regulatory efforts are now gaining momentum and will enable Canadians and fintechs to benefit from the following trends:

Banking as a service describes a model where regulated financial institutions integrate their digital banking services offering directly into the products of other non-regulated entities. This allows retailers and merchants with a strong brand presence to offer their customers digital banking products (debit cards, loans, etc.) without having to incur the substantial costs of obtaining a banking licence. Although the banking as a service offering is currently not as widespread in Canada as in other jurisdictions, this may change as a result of Canada’s plan to give banks greater flexibility to engage with fintechs, to modernise its payment systems and to introduce an open banking framework.

The high number of SMBs in Canada have a significant impact on our economy; their vulnerabilities to downturns such as the pandemic highlight the importance of collaboration between financial institutions, businesses and government to develop fintech solutions to support this segment of the economy. As SMBs reopen following the pandemic, they will be very receptive to new digital platforms enabling them to better, and more profitably, serve their customers.

The fintech lending sector – and, in particular, the Buy Now Pay Later offering, which already has a strong presence – in Canada is expected to continue growing. The non-bank lending platforms (sometimes offered in partnerships with regulated entities) offered by retailers provide consumers an alternative payment method to pay for goods and services allowing them to pay in instalments, generally without fees or interest. Very attractive from a retailer and customer perspective, these products can be challenging from a regulatory perspective, and could result in more scrutiny from regulators as they continue to thrive in the marketplace.

The Canadian fintech ecosystem is internationally competitive. In a recent report, Toronto ranked in 8th place among global cities, while Vancouver, Montréal and Calgary placed 12th, 14th and 16th, respectively1.

From coast to coast, fintechs are relatively well distributed across Canada (based on population concentration). 415 fintechs are based in Ontario, 103 are based in Québec, 165 are based in Western Canada (with the vast majority of those based in British Columbia) and 14 are based in the Atlantic provinces2.

Canadian jurisdictions are also seeing significant in-bound investment from fintechs. Montréal, is one of Canada’s leading fintech hubs, and houses a number of key investors. While the Atlantic provinces have relatively smaller hubs, there is significant activity such as a US$2.75 billion acquisition of a St. John’s-based fintech by Nasdaq in late 2019.

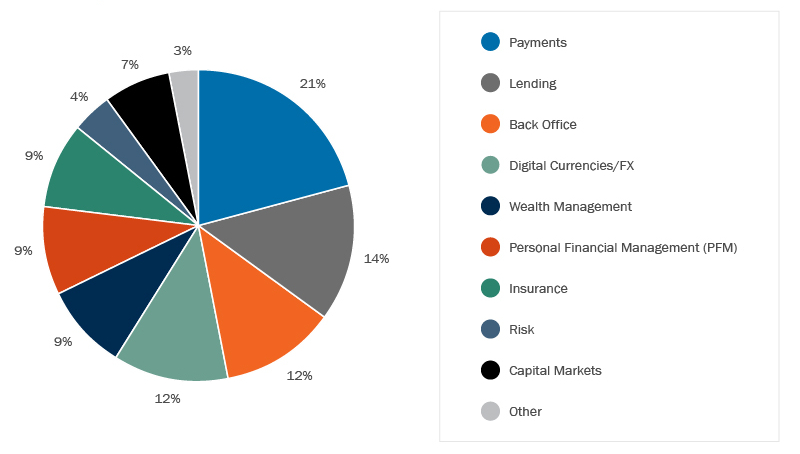

Fintech is a broad term that captures many different verticals. Each of these verticals are large markets in themselves, differentiated by the problems they aim to solve. The most common (and largest) Canadian fintechs categories in operation are Payments, Lending (personal and small to medium businesses), and Back Office. However, fintechs in RegTech (i.e., risk management), WealthTech and Personal Financial Management (PFM) are also seeing significant growth. RegTech startups continue to set funding records, WealthTech activity has seen a significant increase in retail and enterprise activity and PFM has responded strongly to the financial challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, with some PFM fintechs responding particularly well to provide financial support to Canadians in economically uncertain times.

Any healthy startup ecosystem needs accelerators to support the growth of established firms and incubators to nurture the earliest stages of a company. Though competitive to get into, they provide important services for fintech firms such as expert advice, funding, mentorship, networking and training3. The funding for such programs typically come from a variety of sources including financial institutions and technology companies. Well-known accelerators and incubators in Canada include Innovate Calgary, Ryerson’s Digital Media Zone (DMZ), and MaRS Discovery District. DMZ has a specific fintech stream: DMZ-BMO Fintech Accelerator4.

In 2020, CBRE research assessing tech labour and the ability of markets to score tech talent concluded that tech talent is particularly resilient and has proven to be so during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canada has been benefiting from the fintech “brain gain” (the difference between the number of technology degrees granted versus the number of technology jobs created). Toronto ranked fourth just behind San Francisco Bay Area, Washington, D.C. and Seattle, among 50 of the largest markets which were analyzed to create a scorecard ranking them comparatively using metrics like market depth, vitality, and attractiveness to companies seeking talent and talent seeking employment. Data from the Business Development Bank of Canada (2018) has also shown that Canada’s skilled foreign workers as a percentage of its population has been on the rise and is six times more concentrated than that of the U.S. (attributable to a progressive labour migration policy). Though the pandemic did see a drop off in immigration, initiatives such as virtual work permits have been proposed as economic stability returns. Also contributing to domestic growth has been the strength of Canada’s university-backed incubator system5.

The Canadian financial regulatory system is fragmented with oversight of various parts of the financial system divided among a variety of federal and provincial regulators.

The three principal federal regulators of financial institutions are: the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Services (OSFI); the Canadian Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC); and the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (FCAC).

Policy surrounding federal financial services legislation is driven by the Department of Finance and, although they work independently from the Department, OSFI, CDIC, FCAC and the Bank of Canada (BOC) contribute to the development of Canada’s federal financial services legislative and regulatory framework.

Established in 1987, OSFI is an independent agency of the federal government and reports to the Minister of Finance. As Canada’s prudential regulator, OSFI has both a regulatory and supervisory role for more than 400 federally regulated financial institutions and 1,200 pension plans. In its regulatory role, OSFI: develops rules and other guidance; helps to create accounting, auditing and actuarial standards; and provides approvals for certain types of transactions. In its supervisory role, OSFI assesses economic data and trends for issues that could have negative impacts on financial institutions, and, at the same time, assesses financial institutions for weaknesses that could raise solvency or similar critical risks. When such risks are identified, OSFI takes steps to work with an affected institution to address these risks.

In September 2020, OSFI released its discussion paper, “Developing Financial Sector Resilience in a Digital World, selected themes in technology and related risks”, with the objective of engaging stakeholders into a discussion on how OSFI can best position its regulatory framework in a complex, rapidly changing digital world. The paper focuses on the following three main themes:

A federal crown corporation established in 1967, CDIC’s objectives are to:

CDIC provides deposit insurance for eligible deposits up to a limit of C$100,000 per insured category at CDIC member institutions. Members include banks, federally regulated credit unions, as well as loan and trust companies and associations governed by the Cooperative Credit Associations Act that take deposits.

In addition to savings and chequing accounts, CDIC coverage applies to term deposits (including guaranteed investment certificates) and to deposits in foreign currencies. In the event of failure, term deposits and deposits in foreign currencies do not receive separate coverage but would be combined with other deposits within the same category. Notable exclusions from coverage include mutual funds, stocks, bonds, exchange traded funds and cryptocurrencies. While eligible deposits at banks and federally incorporated credit unions are covered, deposits at provincially incorporated credit unions are not; rather, they are covered by provincial insurance corporations aligned to the CDIC model.

CDIC is funded by premiums paid by member institutions and does not receive any public funds to operate.

Recognizing that Canadian banks have been rapidly partnering with fintech firms, as well as adopting their own innovation, CDIC identifies on its website the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s key observations about the impact of fintech on the banking industry. Recognizing that the emergence of fintechs presents a new challenge for CDIC, it reiterates its commitment of actively monitoring the increasing profile of fintechs and the risks they represent to Canadian financial institutions.

Established in 2001, FCAC is Canada’s federal financial consumer protection regulator and ensures federally regulated financial institutions comply with their market conduct obligations under federal legislation, regulations, codes of conduct and public commitments. Although the Payment Card Networks Act (PCNA) also gives the FCAC the authority to supervise payment card network operators (PCNOs), its role is limited in this regard since the PCNA lacks implementing regulations. However, FCAC does supervise PCNOs for compliance with market conduct obligations found in voluntary codes of conduct and public commitments.

FCAC also monitors and evaluates trends and issues that may affect financial consumers, educates Canadians about their rights and responsibilities in dealing with financial institutions, and collaborates with stakeholders to contribute to and support initiatives that strengthen the financial literacy of Canadians.

FCAC’s role as overseer of market conduct obligations is becoming increasingly challenging as existing market conduct obligations which are designed for a “paper-based” world become impractical at best, and unworkable at worst, in a digital world. Unfortunately, the disclosure-heavy approach, which is not aligned with today’s digital world, was preserved in the recent modernization efforts of the federal financial consumer protection legislative framework. Still not yet in force, the new Framework6 consolidates existing consumer provisions and regulations and strengthens consumer protection provisions that apply to banks and authorized foreign banks under the Bank Act. Amendments introduced as part of the new Framework also enhanced FCAC’s powers, most notably by increasing the maximum penalty size available for violations and requiring the FCAC to name institutions following a finding of a violation.

Although not considered a financial institutions regulator, the BOC plays an important role in fostering a stable and efficient financial system. The BOC accomplishes this objective by:

Under the Payment Clearing and Settlement Act, the BOC conducts regulatory oversight of and acts as the resolution authority for designated financial market infrastructures, such as Canada’s Large Value Transfer System (LVTS), the Automated Clearing Settlement System (ACSS) and other clearing and settlement systems, which are owned and managed by Payments Canada, a public-purpose, non-profit organization funded by the members that participate in its systems.

The Bank’s role in Canada’s payment systems is poised to further expand with the recent introduction of the new retail payment oversight framework which is examined in more detail below.

Canada’s financial intelligence unit, FINTRAC, focuses on detecting, preventing, and deterring money laundering and the financing of terrorist activities. FINTRAC fulfils this mandate by engaging in a range of activities including data gathering and analysis (most notably receiving financial transaction reports and voluntary information in accordance with the legislation and regulations) and ensuring compliance by reporting entities with the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA).

Under the PCMLTFA, a “money services business” (MSB) is required to fulfil certain obligations as a reporting entity. This includes registering the MSB’s business with FINTRAC (Canada’s regulator responsible for ensuring compliance with the PCMLTFA), fulfilling reporting and recordkeeping requirements, conducting know-your-client identification, and having a compliance program.

As of June 1, 2021, amendments to the PCMLTFA have expanded the MSB category of reporting entities to include entities dealing in virtual currencies and foreign exchange dealing entities. These amendments bring within scope certain fintechs, both in and outside Canada, that were not previously subject to the PCMLTFA. FINTRAC considers “dealing in virtual currencies” to include both virtual currency exchange services and virtual currency transfer services. These legislative amendments, along with corresponding regulatory guidance from FINTRAC, have significant implications for the regulation of fintechs dealing in digital currencies. In particular, this amendment expands the application of anti-money laundering laws to entities that may not have previously been subject to the PCMTLFA; namely, fintechs (for example, cryptocurrency trading platforms and exchanges).

Under the new rules for foreign MSBs, businesses dealing in virtual currencies without a place of business in Canada who direct their services at persons or entities in Canada and provide these services to clients in Canada are now subject to the PCMLTFA. This change also has implications for virtual currency exchanges as many operate outside of Canada while servicing Canadian clients.

One of the related amendments to the PCMLTFA is the new obligation for all reporting entities to keep “large virtual currency transaction records” for amounts received in virtual currency of C$10,000 or more in a single transaction, or across several virtual currency transactions that equal C$10,000 or more within a 24-hour period. Such records must include the identity of the person from whom the amount was received, as well as other prescribed information including the date, amount and type of currency and exchange rate. Reporting entities must also file large virtual currency transaction reports in certain circumstances, including where the reporting entity receives virtual currency that can be exchanged for C$10,000 or more in cash in the course of a single transaction, or across several virtual currency transactions that equal C$10,000 or more within a 24-hour period. These reports are not required for amounts received from another financial entity or public body, or a person acting on their behalf. As with the expansion of the MSB concept noted above, this amendment to reporting requirements is most likely to impact fintechs.

The OPC administers the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). PIPEDA applies to federal and provincial businesses in respect of personal information collected, used or disclosed in the course of commercial activity, and to the personal information of employees of federal works, undertakings or businesses (such as banks). PIPEDA has extra-territorial jurisdiction to the extent that a foreign organization is handling personal information of Canadians or within Canada. PIPEDA may not apply to certain organizations that process personal information entirely within British Columbia, Alberta and Québec that have substantially similar provincial privacy laws.

PIPEDA incorporates the 10 fair information processing principles contained in the Canadian Standards Association’s Model Code for the Protection of Personal Information. Among these is the core principle that an individual’s knowledge and consent are required for the collection, use or disclosure of personal information except where this knowledge and consent are inappropriate (such as in emergencies, or to comply with court orders).

The OPC can audit organizations to ensure that they comply with the legislation’s requirements. Individuals can file complaints for investigation by the OPC and have the right to apply to court for a hearing and remedies, which may include an award of damages and an order for the business to change its practices. Obstructing the Privacy Commissioner’s audit or investigation is an offence punishable by a fine of up to C$100,000.

Organizations subject to PIPEDA or the Alberta Personal Information Protection Act must notify the regulator and affected individuals of breaches of personal information that create a “real risk of significant harm” to an individual. Organizations must keep internal records of all privacy breaches (even those not reported) for two years, to facilitate regulatory audits and the identification of systemic privacy flaws. Non-compliance with breach reporting obligations can result in fines of up to C$100,000.

The federal government introduced Bill C-11, the Digital Charter Implementation Act, 2020, into Parliament. Bill C-11 proposes to replace PIPEDA with the Consumer Privacy Protection Act (CPPA) and create a new administrative tribunal, the Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal. Among other changes, CPPA proposes to: (a) impose algorithmic transparency requirements; (b) introduce new data subject rights, including the right to data portability (this right aligns with the ongoing Canadian consumer-directed finance proposals); and (c) expand the OPC’s powers, including the ability to impose mandatory orders and to recommend that the Tribunal impose financial penalties of up to C$10 million or 3% of an organization’s gross global annual revenue for contravention of processing provisions and certain security safeguard provisions.

Additionally, at the time of writing, the federal government had recently announced in its 2021 budget that it intends to move forward with plans to create a new federal Data Commissioner role. The government noted that the Data Commissioner’s mandate is to “inform government and business approaches to data-driven issues to help protect people’s personal data and to encourage innovation in the digital marketplace”.

Provincial agencies or administrative bodies responsible for consumer protection oversee the market conduct obligations of provincially incorporated businesses, including provincially regulated financial institutions/services such as mortgage brokering activities, credit unions, and payday lenders. In a 2014 decision, Canada’s Supreme Court held that banks must comply with disclosure requirements under both the federal Bank Act and applicable provincial consumer protection acts. This gives the provinces leeway to impose disclosure requirements on federally regulated institutions as long as such requirements neither conflict with the federal legislation nor the purpose of such (it was previously believed that federally regulated institutions were exempted from such requirements).

Provincial regulators have similar investigative and enforcement tools with which to respond to consumer complaints. Depending on their activities, fintechs are subject to provincial consumer protection law requirements such as provisions in respect of payment card fees, expiry dates and disclosures for open-loop, closed-loop and gift cards, as well as rules with respect to contracts not made in person (e.g., internet contracts).

Enforcement tends to aim at resolution of complaints but can include compliance orders, fines, and prosecution.

Provincial securities commissions regulate the securities markets with a focus on investor protection and ensuring efficient markets. The securities commissions oversee securities trading, registration requirements for participants, continuous disclosure requirements, and enforcement of securities legislation and rules. Self-regulatory organizations also play a role in securities regulation. The Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC), overseeing investment dealers, and the Mutual Fund Dealers Association of Canada (MFDA), regulating mutual fund dealers, are two examples.

Canadian securities regulators have identified as a priority the need to develop and maintain a responsive and aligned regulatory framework to address fintech and other market innovation, while recognising potential benefits and economic opportunities for Canadian businesses that may come from innovation and disruption in the financial services industry. To date, Canadian securities regulators have applied the existing securities regulatory framework to these innovative products and services rather than providing blanket exemptions or exclusions. For example, in 2021, the Canadian securities regulators have taken a number of steps to highlight risks associated with crypto assets, asserting their oversight of crypto asset trading platforms to bring crypto firms engaging in dealer or marketplace activities into compliance with securities laws. This recent work has included developing tailored regulatory approaches to domestic platforms and taking enforcement action against unregistered foreign entities.

Fintech businesses have been encouraged to engage with staff of the Canadian securities regulators through a “regulatory sandbox” to discuss novel products and services, the anticipated treatment under applicable securities laws, and to obtain any required approvals and/or exemptive relief to operate in Canada. Areas where new business models have obtained securities regulatory clearances include peer-to-peer lending platforms, startup and venture introduction and capital raising platforms, and online advisory services. Notably, the Canadian securities regulators have also permitted the establishment of exchange-traded funds that invest in bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, while adopting a restrictive approach to retail distribution of more speculative tokens or initial coin offerings (where compliance with prospectus and dealer/advisor registration requirements is mandated on the basis that these instruments are properly characterized as securities).

The regulatory sandbox is also available for discussions with RegTech services providers developing solutions that support regulated entities in the financial services industry (including regulatory monitoring, reporting and compliance services), although these services would not be subject to the oversight of Canadian securities regulators.

After a slow start in Canada, InsureTech is starting to advance in both the property and casualty and life and health insurance sectors. From underwriting and acquisition, to claims and administration, all aspects of the businesses of each sector are impacted. That said, in 2019 only 12.2% of property and casualty insurers sold insurance through digital channels and only 1.3% of all property and casualty insurance policies were sold online. 46% of life and health insurers sold insurance online with only 1% of policy sales completed online7.

The regulation of insurance in Canada is a matter of shared jurisdiction between the provinces and territories and the federal government. Market conduct and regulatory matters most germane to InsureTech fall to provincial/territorial regulation. This has resulted in a lack of harmonisation across the country in the rules applicable to InsureTech. By way of example, something as simple as the electronic proof of automobile insurance is not uniformly accepted across the country, with some, but not all, provinces having adopted measures to allow drivers to provide electronic proof of insurance on devices such as their smartphones.

Most notably, L’Autorité des marchés financiers, Québec’s financial market regulator, adopted the Regulation respecting Alternative Distribution Methods. The regulation, which came into effect in June 2019, is intended to clarify the rules applicable to insurers and intermediaries selling insurance through digital means. The regulation also requires online aggregators and comparison-shopping sites to become licensed as insurance intermediaries under most circumstances. The regulation is unlike any other presently in effect in Canada. While intended to support innovation and new distribution approaches, the regulation is prescriptive, and rule-based, with significant implications for website and application architecture. The effect has been a retreat of some online and digital insurance offerings previously available in this province.

The Province of British Columbia recently enacted amendments to its Financial Institutions Act. These amendments, among other things, allow the BC regulator to make rules regarding insurance issued through “electronic agents”. Those rules have not yet been released for public consultation and it is unclear if they will align with the regulation that has been adopted in Québec.

The principles for the “Fair Treatment of Customers”8 remain the primary stated concern of market conduct regulators across the country. The regulatory expectations are that both insurers and intermediaries must embed into their operations and cultures principles for the fair treatment of customers9. These principles must be applied before a contract is entered into and through to the point at which all obligations under the contract have been satisfied. While these are the stated regulatory expectations, no specific laws or regulations have been adopted to explicitly incorporate the core principles into enforceable and clearly articulated requirements. The expectation applies to both InsureTech and traditional approaches and channels.

In September, the Digital ID and Authentication Council of Canada (DIACC) launched the Pan-Canadian Trust Framework (PCTF), a set of digital ID and authentication industry standards that will define how digital ID will roll out across Canada. The alpha testing will inform the launch of DIACC’s PCTF Voila Verified Trustmark Assurance Program, set to launch sometime in 2021.

The Ontario government has also announced plans to roll out an optional digital ID for business and individuals in late 2021.

Recognising the imperative for a modern payment system that is fast, flexible secure and promotes innovation, the federal government and Payments Canada are currently leading four significant initiatives which will further accelerate the growth of the Canadian fintech ecosystem.

As part of the 2018 Federal Budget, the Bank Act (Canada), Insurance Companies Act (Canada) and Trust and Loan Companies Act (Canada) were amended to support innovation and competition in the Canadian financial sector.

These amendments will provide Canadian federal financial institutions with broad new powers to: provide referrals of their customers to fintechs; engage in collecting, manipulating and transmitting information, as well as to engage in a broad range of technology-related activities without any regulatory approval (subject to potential restrictions in regulations); commercialise activities developed in-house and provide them to third parties (subject to potential restrictions in regulations); and invest in entities a “majority” of whose activities consist of financial services activities that a financial institution is permitted to carry on (subject to new regulations that will define the meaning of majority and may impose other restrictions).

We would note that while these amendments have been passed, they will not come into force until accompanying regulations are published. As of the time of writing, drafts of those regulations have not yet been published and our expectation is that these provisions will not come into force until at least mid-2022.

With an estimated 3.5 to 4 million Canadians already using data-driven services to manage their finances, most often sharing their data through screen-saving, the federal government recognises that open banking is here to stay and is currently developing its open banking framework. In 2018, the Minister of Finance appointed the Advisory Committee on Open Banking (Committee) to review the merits of open banking. In 2020, the Minister of Finance released the Committee’s first phase report, “Consumer-directed finance: the future of financial services” (report), which announced that the government will move forward to enable consumer-directed finance10. The Committee recommended that Canada’s consumer-directed finance should:

At the end of 2020, the Committee held its phase two consultations with stakeholders that focused on: (a) identifying potential solutions and standards that enhance consumer privacy and security; and (b) the role of a regulator. In May 2021, the Committee presented its second consultation report to the Minister of Finance, who, as of the time of writing, has yet to release the report publicly.

Established by the Canadian Payments Act (the CPA) in 1980, Payments Canada is a non-profit organisation funded by the banks and other deposit-taking institutions. Its legislated mandate includes the following objectives:

The CPA also authorises Payments Canada to set rules for the daily operations of participants in its national clearing and settlement systems. The Minister of Finance is granted a range of powers, including to issue directives to make, amend, or repeal a bylaw, rule, or standard.

Payments Canada is in the midst of a multi-year modernisation programme to ensure that Canada’s payment infrastructure is equipped to support innovation, the economy and Canada’s global position. Payments Canada’s Modernization Plan focuses on three deliverables.

In 2020, Payments Canada completed the upgrades to Canada’s existing retail batch system, the ACSS and the U.S. Bulk Exchange, which runs parallel to the ACSS. The work included refreshing existing functionalities and business processes and introducing new and efficient capabilities, such as:

The LVTS is expected to be replaced in 2021 by the new LYNX system. LYNX will be a real-time gross settlement system that enables the use of the data-rich ISO 20022 messaging standard and includes an enhanced risk model to comply with Canadian and international risk standards.

Operated by Payments Canada and to be regulated by the BOC, Canada’s new RTR to be launched in 2022 will allow Canadians to initiate payments and receive irrevocable funds in seconds at any time. The RTR will have two main components: the RTR Exchange; and the RTR Clearing and Settlement. The RTR Exchange will facilitate the real-time exchange of payment messages, while the RTR Clearing and Settlement will perform the real-time clearing and settlement of transactions. The RTR will provide for immediate benefits, including:

The use of the ISO 20022 standard represents an opportunity for payment service providers (PSPs) to better understand user behaviour through data analytics, implement safeguards against potentially fraudulent behaviour (through more robust fraud detection algorithms), and develop new customer-facing services or products that are responsive to customer needs. For now, direct participation in the RTR will be available only to financial institutions and members of Payments Canada.

The Department of Finance, however, has proposed to expand the scope of membership to include PSPs but only after the implementation of the new regulatory regime for payments service providers which is examined below.

In April 2021, the federal government took the first step in creating a new regime for PSPs when it tabled the long-awaited Retail Payments Activities Act (RPAA). The BOC, who will take on the role of regulator, will oversee “any retail payment activity that is performed by a payment service provider” with a place of business in Canada or by a PSP outside of Canada but which directs retail payment activities for a Canadian end user (natural persons and businesses). A “retail payment activity” is defined as a “payment function” that is performed in relation to an electronic funds transfer made in Canadian currency or the currency of another country or using a unit that meets prescribed criteria. A “payment function” means:

Equally as key as to whom the RPAA applies, is who is specifically excluded from its application:

Where the RPAA applies, PSPs will have to register with the BOC before engaging in retail payments activities, and provide prescribed information including details on the scope of their business and the services they plan on providing, the number of end users, the safeguard mechanisms for any funds held on behalf of users, a declaration as to whether it is registered with FINTRAC, and details on their mandatory operational risk and incident response framework.

PSP applications may be rejected for national security reasons, if they are incomplete or contain false or misleading information or if a PSP is not registered as a money services business under the PCMLTFA.

PSPs will be subject to three key requirements:

The RPAA also provides the BOC with a range of enforcement tools to verify and encourage compliance, including administrative and monetary penalties up to a maximum of C$10,000,000. Since a PSP will be responsible for the acts committed by its employees and its third-party service providers, it will important that the PSP establish the appropriate oversight mechanisms to address these risks.

In response to the rising popularity of digital tokens or cryptocurrencies, like many central banks, the BOC has been working with industry and academia to design a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) as a protective measure against decentralized technologies that challenge the traditional monetary policy transmission systems11. The BOC has confirmed that it is well into the development process of a CBDC and is exploring the challenges and opportunities of CBDCs, but sees no rush in implementing one anytime soon12. Some important policy considerations the BOC has expressed are safety, universal accessibility, privacy, resilience, competition and efficiency, and monetary sovereignty13. It is also important to consider the legal safeguards for data protection when data is concentrated in the hands of a single entity. The BOC issued a policy note in 2020 discussing the spectrum of CBDC privacy concerns and some potential solutions, though nothing has officially been decided on yet14.

In order to implement a CBDC, the BOC, as well as other central banks, must seek legislative amendments to current laws and regulation. Even if a digital banknote is a “banknote” that may be issued by a central bank under its note-issuing power15, legislation and regulation as to distribution and transfers must be passed, defining the roles of commercial banks in the process. Legal tender legislation must also be reviewed. The International Monetary Fund has affirmed the importance of properly legislating the necessary domestic legal reforms to issue CBDCs in order to establish strong legal foundations ensuring the continued integrity of monetary law and policies16.

The Bank of International Settlement recommends17 that CBDCs would best function in a system where central banks and the private sector collaborate, which will encourage commercial banks, credit companies, and digital payment processors to work in partnership with central banks and governments in designing Canada’s digital economic future18. Aligned with this recommendation, the BOC will work closely with stakeholders, including the private sector, to help inform the design of Canada’s CBDC.

Contributors

Peter A. Aziz

Peter A. Aziz Jill E. McCutcheon

Jill E. McCutcheon Glen R. Johnson

Glen R. Johnson

Ronak Shah

Marissa A. Daniels

Marissa A. Daniels

William R. Walters

Eli Monas

Eli Monas

Marko Trivun

This piece was first published by Global Legal Insights as the Canada chapter in the “Fintech Laws and Regulations 2021” publication. You can view the original piece here.