2018 year in review: Top 10 food regulatory and legal issues in Canada

Authors

Eileen M. McMahon

Eileen M. McMahon Yolande Dufresne

Yolande Dufresne Sue Fei

Sue Fei

Denise Ramsden

2018 was an eventful year in Canada’s food regulatory space. A number of changes and proposed changes were introduced throughout the year, including the release of the long-awaited Safe Food for Canadians Regulations 1 (SFCR), the publication of proposed regulations to permit and regulate edible cannabis, and continued efforts in modernizing Canada’s food labeling requirements.

Below is our list of the top 10 food regulatory issues in Canada in 2018 and what to watch for in 2019.

1. Safe food for Canadians regulations

Topping our list is the June 13 release of the finalized SFCR, which had been in development since 2012 following the enactment of the Safe Food for Canadians Act 2 (SFCA). Together, the SFCA and SFCR came into force on January 15, 2019, and introduced the most significant changes in decades to Canada’s legal framework for food products.

The SFCR overhauled the existing regulatory framework for food products, replacing 14 separate sets of regulations (e.g., Dairy Product Regulations, Egg Regulations, Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Regulations) with one set of comprehensive regulations. The new consolidated regulations are based on international food safety standards, which are also the basis for modernized food safety regulations that have been adopted by the United States. In addition to eliminating unnecessary administrative burden on businesses and improving consistency across all types of food and food businesses, the SFCR contain three fundamental new elements: licensing, preventive controls, and traceability.

The SFCR establish a comprehensive licensing framework and require food businesses that engage in the following activities to be appropriately licensed:

- import/export food;

- slaughter food animals or prepare food to be exported or sent across provincial/territorial borders; or

- store and handle meat products that require Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) inspection.

The SFCR set out the key food safety control principles and outline the requirements for developing, implementing and maintaining a written preventative control plan (PCP). The PCP is intended to document how the business would meet the requirements of food safety, humane treatment of animals and consumer protection.

The SFCR also require businesses to trace food products one step forward and backward to the immediate customer or supplier respectively.

Some aspects of the SFCA and SFCR are effective immediately, while other requirements will be phased in over a period of 12 to 30 months. Relevant businesses should review the rules carefully as the compliance date varies based on the food commodity, type of activity and business size.

2. Front-of-package (FOP) labeling consultations

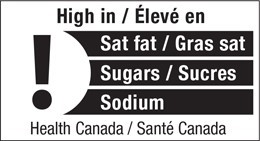

Based on draft regulations published February 10, Health Canada is proposing to implement a system of symbols to be included on the front label of certain food packages that are “high” in saturated fats, sugars and/or sodium. Four proposed standardized symbols were published for public consultation, along with the proposed regulatory amendments to the Food and Drug Regulations (FDR).

Proposed symbols:

The symbol ultimately selected will be included in the final Regulations, published in the Canada Gazette, Part II. Notably, while the final symbol will be included in the Regulations, the Directory of Nutrition Symbol Formats will be incorporated by reference, which enables Health Canada to make further changes to the format without regulatory amendment.

The proposed threshold for “high” is set at a targeted nutrient composition over 15% of that nutrient’s daily value (DV), as determined against the reference amount or stated serving size. The proposed regulations include a number of deviations from the 15% DV threshold for certain food types and package sizes as well as exemptions for certain product classes. Proposed exemptions include, for example, alcoholic beverages, certain raw single ingredient meat and seafood products, and products sold by small businesses at locations such as craft shows and farmers’ markets.

The targeted nutrients are those that, from Health Canada’s perspective, pose public health concerns. If implemented, Canada would be one of a handful of countries to have a mandatory FOP labeling regime. Notably, there is no equivalent requirement in the United States. The currently proposed implementation deadline is December 2022, although final regulations have yet to be released so it is unclear whether this timeline will be pushed back or whether substantive amendments will be made to the proposal.

3. Edible cannabis

Recreational cannabis was legalized in Canada on October 17 to permit authorized persons to sell dried cannabis, cannabis oil, fresh cannabis, cannabis plants and cannabis plant seeds. On December 22, the federal government published the proposed amendments to the Cannabis Act 3 and Regulations 4 to legalize three additional classes of cannabis for sale by authorized persons—edible cannabis, cannabis extracts, and cannabis topicals.

The proposed regulations define edible cannabis as cannabis products intended to be consumed in the same manner as food/beverages. The proposed regulations require edibles to be shelf stable and to include only those food ingredients and additives authorized under the FDR. The proposal generally prohibits meat, poultry and fish as ingredients of edibles, but contemplates exceptions for certain dried meat, poultry and fish obtained from licensed suppliers. The proposal further imposes limitations on the caffeine and alcohol content of edibles and, among other packaging and labelling requirements, requires a simplified nutrition facts table on the packaging of edibles. Further, to process, package and label edible cannabis, companies would need a federal cannabis processing license.

The proposed amendments include many concepts and measures drawn from the SFCA.5 The proposed amendments are open to comments until February 20, 2019 and may change before final regulations come into force on or before October 17, 2019.

4. Food Labelling Modernization still on its way

In a continuing effort to achieve Food Labelling Modernization (FLM) in Canada, the CFIA completed another round of consultations on proposed labelling requirements. The CFIA solicited and published responses to a discussion paper detailing the proposed approach to modernized food labelling, drafted by the CFIA. Stakeholders provided feedback on a variety of proposed labelling requirements, including: date marking compliance with international standards under Codex Alimentarius, format standards aimed at improving legibility, ingredients highlighted in claims or pictures to be specified in the ingredients list, modernized food company information (updating from mailing addresses to toll-free numbers and website contacts), addition of labeling statements noting the origin of wholly imported food, harmonizing common names and classes with the Codex and U.S. standards, and deregulating standard container sizes for certain products.

There was general consensus from consumers and industry alike regarding the need for more transparency and legibility around food ingredients, including significant support for requiring “flavour” or “flavoured” be printed in the same font and size as related text, when the real ingredient is not present. While consumers were largely in support of implementing legibility label requirements, including improving the prominence of the common name, industry expressed concern regarding the limited space on labels. Industry stakeholders generally supported modernizing the company information included on the label, however, they expressed concern regarding a proposal to include the CFIA license holder’s information on the label. Given the array of different manufacturing and licensing arrangements, stakeholders prefer to continue including the information of the entity responsible for the product, even if they are not the license holder. The CFIA has indicated the feedback will be taken into consideration in the drafting of finalized regulations. No deadline for their publication has been released.

5. Proposed amendments to the Food and Drug Regulations, Part B, Division 2 (Beer)

Canada’s federal government released the proposed amendments to the FDR, Part B, Division 2 (Beer) on June 16. The proposal is aimed at redefining the compositional standard for beer, to better reflect the innovation and market developments of the Canadian brewing industry. This will be the first major amendment to the beer standard under the FDR in the past 30 years.

The proposed amendments will eliminate duplication of composition standards and set one standard for all types of beers regardless of style. Rather than listing each specific food additive in the beer standard, the proposed standard will refer to the Lists of Permitted Food Additives maintained by Health Canada as the one source of information on permitted food additives. To allow innovation and market developments, the proposal will also expand the definition of beer to allow for the use of new ingredients and flavouring preparations.

The proposed amendments set a maximum limit on the percentage of residual sugars in beer to be 4%. This is an objective measurement to distinguish beer from other malt-based alcoholic beverages, replacing the current subjective standard of “the aroma, taste and character commonly attributed to beer.” Other elements of the proposal include further clarification of the term “carbohydrate matter,” the removal of processing aids in the standard and the existing food allergens, gluten sources and added sulphites labelling exemption.

The proposed amendments were open to a 90-day consultation period, which closed on September 14. It is anticipated the final amendments may be available the spring of 2019.

6. Revision of Canada's Food Guide

Canada’s Food Guide, maintained by Health Canada, provides healthy eating recommendations based on scientific evidence to help Canadians make food choices. The current version was last updated in 2007. The Canadian government began the consultation process in 2016 to modernize Canada’s Food Guide, aimed at addressing the latest scientific evidence and better reflecting Canada’s changing demographics and lifestyles.

Since 2016, Health Canada has engaged with stakeholders and the public in various ways. The latest open consultation took place in the summer of 2017. In March 2018, Health Canada published the “Canada's Food Guide Consultation—Phase 2 What We Heard Report,” summarizing feedback from approximately 6,700 contributors regarding the proposed general healthy eating recommendations. According to the report, the proposed principles and recommendations on healthy eating were well received overall. However, a number of concerns were raised by contributors, such as how the general recommendations would be positioned in guidance materials to be distributed to the public, access to healthy foods and the affordability of following the recommendations.

Taking into account the feedback received, subject to delays, the new dietary guidance policy report for health professionals and policy makers is expected to be released in two parts in 2019. Part 1 on general healthy eating recommendations is expected in early 2019 and Part 2 on healthy eating patterns is expected in late 2019. Supporting key messages and resources for Canadians are also expected to be released in the same year.

7. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) in pre-market submissions for genetically modified plants

In March, Health Canada and the CFIA jointly released a new guidance document on the use of WGS to generate data for pre-market submissions for genetically modified plants. This was in response to industry request for guidance on this issue and arguably signals that Health Canada and the CFIA are becoming more receptive to such data.

High-throughput sequencing has undergone rapid development in the past decade and commercial platforms are now more affordable, reliable, and accessible. There is widespread adoption of WGS in biological, medical and agricultural research, clinical diagnostics, and epidemiology and consequently, there has been a rise in popularity in industry’s use of WGS-generated data in regulatory submissions. The guidance document provides industry with clarification on the information related to the WGS study design and methodologies, data analysis and presentation that is expected if a regulatory submission uses WGS-generated data. For example, the guidance indicates that manipulations applied to the WGS-generated sequence data need to be explained and excluded sequence from analysis needs to be justified.

While this guidance document provides more clarity in using WGS-generated data for pre-market submissions for genetically modified plants, it is important to note that the use of WGS technology is optional. Industry may continue to use data generated using traditional molecular biology methods for the purpose of premarket submissions.

8. Foreign regulatory reviews may be relevant in Canada

As part of its Fall Economic Statement, the Canadian federal government announced plans to establish a modernized food approval avenue in an effort to establish a faster route to market for certain products. If the current proposal was implemented, foreign regulatory reviews, in addition to other information and documents that may be required by the CFIA, could be considered and relied upon in the Canadian authorization process for certain products like food processing aids and food additives. This proposal is aimed at fostering the development of innovative products and ensuring Canada remains competitive in the global economy. To date, no concrete regulatory scheme has been published by the federal government.

9. Limited duty of care to exporters owed by the CFIA

In addition to regulatory changes, there were also a number of interesting Canadian case law developments in 2018. For example, aspects of the CFIA’s liability for negligence were considered by the New Brunswick Court of Appeal. As per the New Brunswick Court of Appeal’s ruling in Cropvise Inc. v Canadian Food Inspection Agency (Cropvise),6 the CFIA may owe a duty of care to Canadian growers and exporters with which it deals. However, that prima facie duty of care can be negated by broader policy and trade relationship matters.

In Cropvise, a shipment of Canadian potatoes, certified by the CFIA as meeting relevant treaty quality standards, was rejected and held by the importing Venezuelan authorities. In upholding the trial judge’s finding, the appeal court found that while the CFIA owed the Canadian exporters a duty of care, to negotiate with the Venezuelan authorities for the release of the potatoes, that duty of care was ultimately negated by policy concerns. The CFIA had attempted to negotiate the release of the shipment with Venezuelan authorities, but remained cognizant of foreign policy concerns in their approach to the negotiation. The court held that it is permissible for the CFIA to attenuate its negotiation efforts regarding the acceptance or release of the shipments on behalf of the Canadian exporters, in view of broader policy concern of preserving the trade relationship with Venezuela and market access to foreign nations. This issue was not considered by Canada’s highest court, the Supreme Court of Canada, and the opportunity to seek leave to appeal has passed.

10. The CFIA’s limited exposure to damages

The CFIA’s liability was also considered by the Alberta courts in 2018. The federal agency’s exposure to liability for damages related to its actions is limited by section 9 of the Crown Liability and Proceedings Act (CLPA).7 Section 9 bars claims against the federal government where compensation for damages regarding the same event have already been paid.

In its 2018 decision in North Bank Potato Farms Ltd. v The Canadian Food Inspection Agency,8 the Alberta Queen’s Bench considered whether potato producers, who were erroneously forced to destroy their crop due to a false positive in testing carried out by the CFIA, could claim damages from the agency. In this case, the potato producers received compensation related to the destruction of their potatoes, through the Consolidated Revenue Fund and the Alberta Seed Potato Assistance Program, programs funded at least partially by the federal and provincial government. The fact compensation from the revenue assistance programs was tied to the destruction of the crop due to the presence of cysts, while the claim was based on the false positive and mistaken destruction was an insufficient distinction; both related to the same event for the purposes of section 9 of the CLPA. The court held that claims may be barred under section 9, even if the prior compensation received did not fully redress the loss. Additionally, the court indicated there is no requirement that individuals accepting payments be notified that such acceptance may bar future claims against the Government of Canada.

This piece was originally published by the Food and Drug Law Institute.

_________________________

1 Safe Food for Canadians Regulations, SOR/2018-108.

2 Safe Food for Canadians Act, S.C. 2012, c. 24.

3 Cannabis Act, S.C. 2018, c. 16.

4 Cannabis Regulations, SOR/2018-144.

5 For further discussion on the various facility, testing, packaging, good production practices, quality control, record keeping requirements, THC or CBD limits, and restrictions on ingredients associated with the new cannabis classes imposed by the proposed amendments, see Torys’ publication “Let Them Eat Cannabis — with Restrictions!"

6 2018 NBCA 28.

7 Crown Liability and Proceedings Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. C-50.

8 2018 ABQB 505.