Torys’ Tax Practice

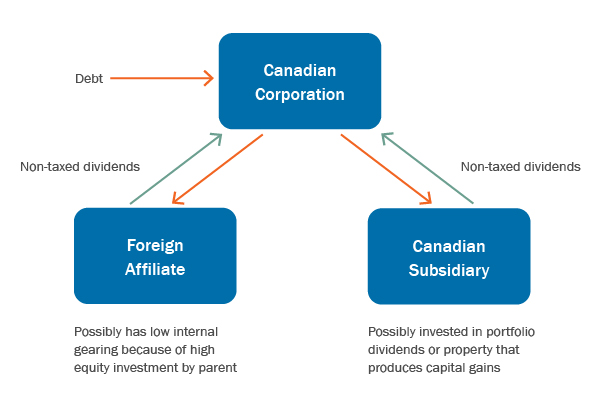

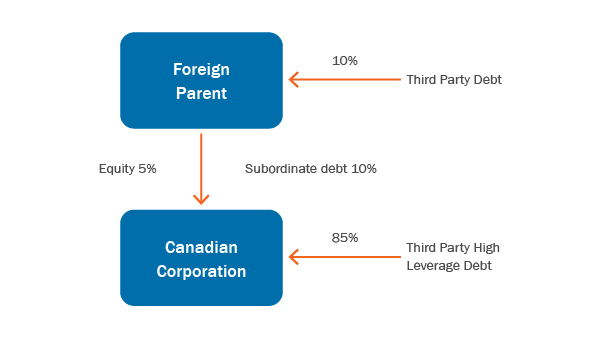

Example 2: Having Canadian businesses bear a disproportionate burden of a multinational group’s third-party borrowings

In this example, a Canadian corporation borrows money to finance its business but has a disproportionate gearing compared to its parent.

(C) The EIFEL rules implement Canada’s commitment to BEPS Action 4

EIFEL is Canada’s response to the OECD’s BEPS Action 4 Report. Canada is a member of the OECD and has committed with other member nations to close gaps in international taxation for companies that are perceived to inappropriately avoid taxation or reduce their tax burden. The Action 4 Report, published in 2015, observed that multinational groups were using interest deductibility rules to reduce their income in higher-tax countries, resulting in tax base erosion for those higher-tax countries. To address this issue, the Action 4 Report offered model rules that countries including Canada could implement to ensure an entity’s allowable interest deductions in a country were commensurate with their level of taxable income from activities in that country. By 2019, 67 countries had interest limitation rules in place, including all European Union member states1.

The EIFEL rules also carry out (in a modified manner) a proposal made in the 2007 Federal Budget (that was later abandoned) to broadly deny an interest expense to Canadian corporations that borrowed to invest in foreign affiliates.

(D) Scope

The EIFEL rules will not apply to the following “excluded entities”:

- individuals;

- CCPCs that, together with any associated corporations, have less than $15 million of taxable capital employed in Canada;

- Canadian-resident taxpayers that are part of a group whose Canadian members have total net interest and financing expenses for the year of $250,000 or less (excluding group members that are financial institutions); and

- a Canadian-resident entity, or group of Canadian-resident entities, that carry on all or substantially all of their business in Canada, provided that:

- there are no foreign affiliates;

- none of them has a non-resident specified shareholder or specified beneficiary; and

- all or substantially all of their interest and financing expense are paid or payable to persons or partnerships that are not tax-indifferent investors (which does not include tax-exempt persons or non-residents—meaning that the interest income would be within the Canadian tax net).

(E) Highlights of the EIFEL rules: fixed vs. group ratio

The EIFEL rule consists of a default fixed ratio rule of 30% (40% for 2023) and an optional group ratio rule that can potentially allow a higher ratio where a group has a higher borrowing ratio in its overall business as reflected on its consolidated financial statements.

Taxpayers will generally have the option to annually elect to apply the group ratio rule if it would allow more interest to be deductible.

(F) Fixed ratio rule

The Proposals contain a fixed ratio rule that tests each entity on a stand-alone basis based on its net interest and financing expenses and adjusted taxable income. The rule itself determines a proportion of the taxpayer’s total interest that is denied. Generally, that proportion is based on the following formula:

| interest and financing expenses for the year | minus | interest and financing revenue for the year | minus | 30% (40%) of adjusted taxable income for the year |

| interest and financing expenses for the year | ||||

A taxpayer can avoid having a disallowance if it can get the numerator in the formula to be zero. The numerator starts with the taxpayer’s interest and financing expenses. It is then reduced by the “interest and financing revenue” of that entity for the year. Accordingly, every dollar of interest and financing revenue creates a dollar of interest expense room. The numerator is further reduced by 30% (40% in 2023) of the taxpayer’s adjusted taxable income. Accordingly, every dollar of adjusted taxable income creates 30% (or 40%) of a dollar of interest expense room. If the numerator remains positive, a fraction will be computed, and will result in a denial of a portion of the taxpayer’s interest expense (subject to certain adjustments to carry excess interest capacity forwards and to share it within a group and for the carryforward of denied interest expense from other years).

The application of the fixed ratio rule can best be illustrated by way of example:

Example 1

If a corporation has interest and financing expenses in the year of $10, no interest and financing revenues and an adjusted taxable income of $30, then the proportion of interest expense that will be denied will be:

($10 – (30% x $30)) / $10 = 10% ($1)

Example 2

If a corporation has interest and financing expenses in the year of $10, $10 of interest and financing revenues and no adjusted taxable income, then the proportion of interest expense that will be denied will be:

($10 – $10) / $10 = nil

Example 3

If a corporation has interest and financing expenses in the year of $10, $4 of interest and financing revenues and an adjusted taxable income of $30, then the proportion of interest expense that will be denied will be:

($10 – $4 – (30% x $30)) / $10 = nil

The second and third examples illustrate that the corporation will have sufficient interest and financing revenues and adjusted taxable income to shelter its interest and financing expenses such that no interest and financing expenses will be denied under the fixed ratio rule. The corporation in the first example, however, will have 10% of its otherwise deductible interest and financing expenses denied.

(i) The applicable definitions

The EIFEL Rules apply to more than just interest and can also deny amounts that are perceived to be equivalent to interest or that can be considered related to the cost of borrowing including derivatives.

“Interest and financing expenses” generally include:

- amounts paid or payable in a year as, on account of, in lieu of payment of or in satisfaction of, interest;

- interest and financing expenses that are “capitalized” and deducted as capital cost allowance or as amounts in respect of resource expenditure pools;

- an imputed amount of interest in respect of certain finance leases;

- deductible payments under derivatives entered into as or in relation to a borrowing and that can reasonably be considered part of the cost of funding; and

- various expenses incurred in obtaining financing.

“Interest and financing revenues” generally include:

- amounts received or receivable as, on account of, in lieu of payment or in satisfaction of, interest (other than excluded interest);

- guarantee fees; and

- amounts received under a derivative entered into as or in relation to a debt receivable and that can reasonably be considered to increase the taxpayer’s return from the receivable.

“Adjusted taxable income” is essentially the taxpayer’s earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, adjusted for tax purposes. It starts with either: (i) the taxpayer’s taxable income minus any net capital loss; or (ii) its non-capital loss plus any net capital loss. It then adds back, amongst other things, interest and financing expenses (other than capitalized interest) and capital cost allowance and subtracts out interest and financing revenue and tax-exempt income (i.e., foreign-source income to the extent it is sheltered from Canadian tax by foreign tax credits).

(ii) Excess capacity and transfers to members of Canadian group

The Proposals contain detailed rules that allow flexibility in how the EIFEL is applied and are generally intended to smooth the impact of earnings volatility year-to-year. These rules rely on the concept of “excess capacity”, which is generally the amount by which the maximum amount an entity is permitted to deduct in respect of interest and financing expenses for the year (i.e., 30% of its adjusted taxable income plus its interest and financing revenues for the year) exceeds its actual interest and financing expenses for the year.

Provided that a taxpayer has not applied the group ratio rule (discussed below), it can apply its “excess capacity” in the three preceding taxation years to allow for the deduction of otherwise denied interest and financing expenses for the current taxation year. The transitional rules allow for excess capacity to be calculated for years prior to the EIFEL rules taking effect.

There is also a mechanism that allows for some or all of a taxable Canadian corporation’s excess capacity to be effectively transferred to members of a Canadian group that are also taxable Canadian corporations by way of an election. Note, however, that financial institutions are generally prohibited from transferring excess capacity to other group members. Moreover, a taxpayer is required to use its own excess capacity carryforwards first to deduct its own otherwise denied interest and financing expenses, before it can transfer any remaining excess capacity to another group member by way of an election.

The rules also allow for the carryforward of denied interest and financing expenses. Interest and financing expenses of an entity that are denied under the EIFEL rules can generally be carried forward twenty years to be deducted in years that the entity has excess capacity.

(iii) Partnerships

Similar to the approach under the thin capitalization rules in the Tax Act, the EIFEL rules also apply indirectly in respect of partnerships, as interest and financing expenses and revenues of a partnership are attributed to members that are corporations or trusts, in proportion to their interests in the partnership. Where a taxpayer has excessive interest and financing expenses, the EIFEL rules will include an amount in the taxpayer’s income in respect of the taxpayer’s share of partnership interest and financing expenses.

(iv) Excluded interest

The EIFEL rules generally allow taxable Canadian corporations that are related or affiliated with one another to jointly elect that one or more interest payments made by one to the other in a taxation year be excluded from the new interest limitation. The purpose for allowing this exclusion is to ensure that certain common loss consolidation transactions are not negatively impacted by the application of the EIFEL rules.

(v) Continuity rules

Certain proposed amendments to the amalgamation and wind-up provisions in the Tax Act will generally allow for restricted interest and financing expense carryforwards and excess capacity to be inherited by the new corporation formed on an amalgamation or the parent corporation in respect of a wind-up.

A taxpayer’s carryforwards of restricted interest and financing expenses generally remain deductible following a loss restriction event, to the extent the taxpayer continues to carry on the same business following the loss restriction event. However, a taxpayer’s cumulative unused excess capacity does not survive a loss restriction event.

(G) Group ratio rule

The group ratio rule permits a greater ratio for members of a “consolidated group” whose audited financial statements show a ratio of third-party interest to book EBITDA in excess of the fixed ratio. This might allow a higher deduction for some entities in that group than would otherwise be available under the fixed ratio rule.

(i) Criteria for using the group ratio

Generally, a consolidated group means two or more entities which are required to prepare “consolidated financial statements” (as defined in the Proposals, but generally meaning financial statements in which the assets, liabilities, income, expenses and cash flows of two or more entities are presented as those of a single economic entity), or would be so required if the entities were subject to IFRS.

Canadian group members (generally, Canadian corporations and trusts with a sufficient connection between them) within a consolidated group can file an election to use the group ratio rule provided they meet certain criteria, including:

- each Canadian group member is a taxable Canadian corporation or a trust resident in Canada;

- each Canadian group member has the same taxation year and reporting currency;

- no Canadian group member is a “relevant financial institution”; and

- the consolidated financial statements of the consolidated group for the year are audited.

We note that the definition of “relevant financial institution” is very broad. For example, it includes entities such as banks and credit unions, but also corporations whose principal business is the lending of money to arm’s length persons, MFTs and mutual fund corporations.

(ii) Calculating the group ratio

The group ratio is determined using the following formula:

| Group net interest expense |

| Group adjusted net book income |

If the formula results in a ratio above 40%, only 50% of the excess over 40% can be used to increase the group ratio (e.g. if the formula results in 50%, the group ratio is 45%). If the formula results in a ratio above 60%, the group ratio is deemed to be 50%, plus 25% of the excess over 60% (e.g., if the formula results in 100%, the group ratio will be 60%). The group ratio cannot exceed 100%.

Once the group ratio is determined, the ratio is multiplied by the adjusted taxable income of all the Canadian group members. That results in the total amount that may be allocated to the Canadian members in the group, and the group is permitted to allocate that amount amongst the Canadian members in the group in whatever manner they desire, provided that the total amount allocated to all the Canadian group members does not exceed the group net interest expense and the amount allocated to any particular member does not exceed that member’s adjusted taxable income. The amount allocated to the member is then used to determine the permitted interest expense of the member, and replaces the 30% of adjusted taxable income in the formula above.

The group net interest expense is the amount by which the consolidated group’s “specified interest expense” (which is based on amounts reported on the consolidated financial statements and includes interest expense and guarantee fees, standby charges and arrangement fees that are paid by the group and the group’s share of such expenses of an entity that the group recognizes through equity accounting) exceeds its “specified interest income” (which is based on amounts reported on the consolidated financial statements and includes interest income and guarantee fees, standby charges and arrangement fees that are received by the group and the group’s share of such income and fees of an entity that the group recognizes through equity accounting). The provisions back out interest expense or income paid to or received from a person or partnership that is not a member of the consolidated group but that does not deal at arm’s length or has a substantial equity interest in the group.

The group adjusted net book income is comparable to the consolidated group’s EBITDA, with various adjustments. Income tax, most “specified interest expense”, charges for the impairment or write-off of fixed assets and losses from the disposition of fixed assets are added back. There is then a deduction for various income and receipts that mirror the items required to be added back (e.g., income tax receivables and specified interest income).

(H) Application

The EIFEL rules apply after existing limitations on the deductibility of interest and financing expenses in the Tax Act, including the thin capitalization rules. Any expenses whose deductibility is denied under such existing limitations are excluded from a taxpayer’s interest and financing expenses for purposes of the new rules.

There is no transitional relief for existing debt or financing arrangements.

(I) Anti-avoidance rules

The EIFEL Rules contain a number of anti-avoidance rules meant to prevent abuse.

- Short taxation years: The application of the EIFEL rules will be accelerated if: (i) the taxpayer had a “short” taxation year in any of the three taxation years immediately preceding the first taxation year that begins on or after January 1, 2023; and (ii) one of the purposes of the short taxation year is to defer the application of the EIFEL rules, or increase the taxpayer’s excess capacity for a year prior to 2023.

- Symmetrical treatment of interest and financing revenues for non-arm’s length parties: The EIFEL rules require symmetrical treatment of amounts received or receivable by a taxpayer from a non-arm’s length person or partnership. Therefore, if an amount is not included in the interest and financing expenses of the payer, it will also not be included in the payee’s interest and financing revenues.

- Interest and financing expenses: An amount that would otherwise not be included in a taxpayer’s interest and financing expenses will be included if: (i) the amount arose in the course of a transaction; and (ii) one of the purposes of the transaction was to prevent the amount from being included in the taxpayer’s interest and financing expenses for the year.

- Interest and financing revenues: An amount that would otherwise be included in a taxpayer’s interest and financing revenues will not be included if: (i) the amount arose in the course of a transaction; and (ii) one of the purposes of the transaction was to increase the taxpayer’s interest and financing revenues in order to obtain a tax benefit for any taxpayer.

- Excluded entity: One of the criteria to be an “excluded entity” (discussed in more detail above) requires that all or substantially all of a taxpayer’s interest and financing expenses must be paid or payable to persons or partnerships that are not tax-indifferent investors. A person or partnership will be deemed to be a tax-indifferent investor if: (i) an amount of interest and financing expenses is paid or payable to that person or partnership as part of a transaction; and (ii) one of the purposes of the transaction was to avoid that amount being paid or payable to a tax-indifferent investor.

Mandatory disclosure rules

Budget 2021 proposed several new measures to enhance the mandatory disclosure regime in the Tax Act. These measures are intended to provide the CRA with more robust disclosure to respond quickly to aggressive tax planning, either through informed risk assessments, audits or changes to legislation. The Proposals introduce draft legislation to implement the measures announced in Budget 2021. The draft legislation expands the scope of the current reportable transaction rules, as well as proposing new disclosure requirements for “notifiable transactions”, and in the case of certain corporate taxpayers, “uncertain tax positions”. The Proposals will apply to taxation years, and transactions occurring in taxation years, that begin after 2021, although the penalty provisions (and in the case of the reportable transaction rules, the revised penalty provisions) will not apply to transactions entered into before the date on which the Proposals receive Royal Assent.

(A) Reportable transactions

The Tax Act currently contains rules in section 237.3 of the Tax Act that require certain transactions entered into by, or for the benefit of, a taxpayer to be reported to the CRA. More specifically, these rules generally apply if: (i) there is an “avoidance transaction” (as defined in the GAAR provisions in section 245 of the Tax Act) or a series of transactions that includes an avoidance transaction; and (ii) two of the following three prescribed hallmarks are present:

- a promoter or advisor is entitled to fees in respect of the avoidance transaction or series that are contingent on the amount or obtaining of a tax benefit or on the number of taxpayers who participate;

- a promoter or advisor requires “confidential protection” with regard to the avoidance transaction or series; and

- the taxpayer obtains “contractual protection” in respect of the avoidance transaction or series, which includes any form of “insurance” designed to protect against a failure to achieve the intended tax benefit.

The Proposals revise the reportable transaction rules in two ways to lower the threshold required to engage this regime. First, the draft legislation amends the definition of “avoidance transaction” so that it applies if it can reasonably be concluded that one of the main purposes of entering into the transaction, or of a series of transactions of which the transaction is a part, is to obtain a tax benefit. As described above, the current “avoidance transaction” definition in section 237.3 imports that definition from the GAAR, which requires a transaction to be undertaken primarily for the purpose of obtaining a tax benefit. The Proposals widen the scope of the definition and notably expand the definition beyond that which applies in the GAAR context. Second, the Proposals amend the definition of “reportable transaction” to only require one of the three prescribed hallmarks outlined above to be present in order for a transaction to be considered a reportable transaction.

The Proposals also include an amendment to the definition of “reportable transaction” to provide an exclusion from the reporting requirements for “contractual protection” offered in the context of normal commercial transactions to a wide market. To be excluded, the form of insurance, protection or undertaking has to be “offered to a broad class of persons and in a normal commercial or investment context in which parties deal with each other at arm’s length and act prudently, knowledgeably and willingly”. At this time, the scope of the proposed exclusion is not yet clear. It is possible that the exclusion would cover representations and warranties, and transactional tax, insurance but there is still considerable uncertainty with the lack of administrative guidance on this provision.

Under the Proposals, a reporting obligation will apply to a taxpayer if a tax benefit results to such taxpayer, or is expected to result to such taxpayer based on the tax filing position taken by such taxpayer of the reportable transaction, from: (i) the reportable transaction; (ii) any other reportable transaction that is part of the series that includes the reportable transaction; or (iii) a series of transactions that includes the reportable transaction. The reporting timelines described below become challenging with respect to a series of transactions which includes a reportable transaction, as the timeline to report could start after the first transaction in the series.

The Proposals do not alter the reporting obligations of other persons. In this regard, under current rules, the following persons also have reporting obligations: (i) any person who has entered into, for the benefit of the taxpayer, an avoidance transaction that is a reportable transaction; and (ii) a promoter or advisor in respect of the reportable transaction, or another transaction that is part of the series, who is entitled to a contingent fee or a fee in respect of contractual protection, as each is described in the hallmarks set out above. Further, the exception to the disclosure obligations is maintained for a lawyer who acts as an advisor in respect of a reportable transaction, but only to the extent that solicitor-client privilege applies to the particular information.

Under the current rules, a reportable transaction must be reported to the CRA on or before June 30 of the calendar year following the calendar year in which the transaction first became a reportable transaction. The Proposals greatly accelerate the reporting timelines and require a reportable transaction to be reported to the CRA within 45 days of the earlier of the day the taxpayer (or the person who entered into the transaction for the benefit of the taxpayer) either becomes contractually obligated to enter into the transaction or enters into the transaction. The same reporting deadline applies to any other parties (such as promoters or advisors) required to disclose the reportable transaction. The Proposals require all parties subject to the reportable transaction rules in respect of a transaction to complete the disclosure requirements. In contrast, the current rules allowed disclosure by one party to be treated as disclosure by all relevant parties.

Under current rules, where there is a failure to comply with the disclosure obligations, the GAAR is deemed to apply and the reporting parties will be subject to penalties. The revised consequences of failing to comply with these disclosure obligations, including the increase in the amount of the penalties, is discussed below under the heading “(D) Reassessment period and penalties”.

(B) Notifiable transactions

The Proposals include a new notifiable transaction regime designed to provide the CRA on a timely basis with detailed information relating to specific tax avoidance transactions and other specified transactions of interest (which includes situations in which more information is needed to determine if a transaction is abusive). Under the Proposals, the Minister (with the concurrence of the Minister of Finance) has the authority to designate a transaction as a notifiable transaction. As part of the materials released with the Proposals, the following six types of transactions have been designated by the Minister as notifiable transactions:

- manipulating CCPC status to avoid anti-deferral rules applicable to investment income;

- straddle loss creation transactions using a partnership;

- avoidance of deemed disposal of trust property;

- manipulation of bankrupt status to reduce a forgiven amount in respect of a commercial obligation;

- reliance on purpose tests in the loss restriction rules to avoid a deemed acquisition of control; and

- back-to-back arrangements aimed at circumventing the thin capitalization rules and Part XIII withholding tax.

The Government has released Income Tax Mandatory Disclosure Rules Consultation: Sample Notifiable Transaction2 (Backgrounder) with more details on the types of transactions that would fall within the above list and examples of substantially similar transactions.

The reporting requirements for notifiable transactions are not limited to the sample designated transactions outlined in the Backgrounder. The disclosure requirements also apply in respect of a transaction that is “substantially similar” to a transaction designated by the Minister. Any transaction that is expected to achieve the same or similar tax consequences and that is either factually similar or based on the same or similar tax strategy is considered to be substantially similar. The Proposals note that “substantially similar” is to be interpreted broadly. The substantially similar component of the notifiable transactions regime considerably expands the scope and adds a level of uncertainty to this reporting requirement. In order to comply with these rules, taxpayers will have to make their own determinations on whether transactions are substantially similar to a designated transaction.

The timing for reporting notifiable transactions is the same as the requirements for reportable transactions. A taxpayer who enters into a notifiable transaction or a transaction that is substantially similar to a notifiable transaction is required to report to the CRA within 45 days of the earlier of the day the taxpayer (or the person who entered into the transaction for the benefit of the taxpayer) either becomes contractually obligated to enter into the transaction or enters into the transaction.

A promoter or advisor offering a scheme that would be a notifiable transaction or a transaction that is substantially similar to a notifiable transaction is required to report to the CRA within the same time limits as a taxpayer. An exception to the reporting requirements is available for advisors to the extent that solicitor-client privilege applies.

The Backgrounder notes that the Proposals are intended to provide information to the CRA and do not change the tax treatment of a transaction.

Information returns that are required to be filed for a notifiable transaction must:

- describe the expected, claimed or purported tax treatment and all potential benefits expected to result from the transaction;

- describe any contractual protection with respect to the transaction;

- describe any contingent fees with respect to the transaction;

- identify and describe the transaction in sufficient detail for the Minister to be able to understand the tax structure of the transaction;

- identify the provisions relied upon for the tax treatment in the Tax Act, the Income Tax Regulations, the Income Tax Application Rules, a tax treaty or any other enactment that is relevant in computing tax or any other amount payable or refundable to a person under the Tax Act or in determining any amount that is relevant for the purposes of that computation;

- identify, to the best knowledge of the person who is filing the return, every person required under subsection 237.4(4) of the Tax Act to file an information return in respect of the transaction; and

- provide such other information as is required by the information return.

(C) Uncertain tax treatments

As introduced in Budget 2021, the Proposals set out a new disclosure requirement for taxpayers to report “uncertain tax treatments”. In accordance with IFRS, there is a requirement to report uncertain tax treatments in financial statements. This requirement applies to Canadian public corporations and Canadian private corporations that choose to use IFRS. Under IFRS, when a corporation concludes that it is not probable that the taxation authority will accept an uncertain tax treatment, the effect of that uncertainty is reflected in the financial statements.

The Proposals apply to a “reporting corporation”, which is defined to mean a corporation:

- that is required to file a Canadian income tax return for the taxation year (this includes a corporation that is a resident of Canada or a non-resident corporation with a taxable presence in Canada);

- the carrying value of the corporation’s assets is at least $50 million at the end of the taxation year; and

- that has, or a consolidated group of which the corporation is a member has, audited financial statements prepared in accordance with IFRS or other country-specific GAAP relevant for domestic public companies (e.g., U.S. GAAP).

The Proposals provide that uncertain tax treatments must be reported by the date in which the corporation’s income tax return is due. As well, the Proposals note that reporting an uncertain tax treatment is not an admission that the tax treatment is not in accordance with the Tax Act.

Notably, the proposed amendments fail to acknowledge that some information relating to uncertain tax positions may be privileged. Corporations may seek legal advice in relation to uncertain tax treatments. The Supreme Court has recently treated solicitor-client privilege as a quasi-constitutional principle of fundamental justice in the tax context, and has read down legislation that could be interpreted as compelling the disclosure of solicitor-client privileged information to the Minister for purposes of administering and enforcing tax legislation. If the proposed amendment passes in its current form, courts would need to resolve the inter-relationship between the disclosure of uncertain tax treatments and solicitor-client privilege.

The Proposals did not set out the prescribed information that would be required to report uncertain tax treatments, but the Backgrounder noted that the following information is expected to be included:

- the taxation year to which the reportable uncertain tax treatment relates;

- a description of the relevant facts;

- a description of the provisions relied upon for determining the tax payable, or the refund of tax or other amount under the Tax Act;

- the differences between the tax payable under the Tax Act, or the refund of tax or other amount under the Tax Act, determined in accordance with the corporation’s financial statements and the tax treatment of the corporation;

- whether those differences (outlined in the point above) represent a permanent or temporary difference, involve a determination of the value of property, and involve a computation of basis; and

- such other information required by the Minister.

(D) Reassessment period and penalties

If a taxpayer is subject to one of the mandatory disclosure requirements described above in respect of a transaction that occurred in a taxation year, the Proposals provide that the normal reassessment period will not start with respect to that transaction until the reporting requirement has been met. In effect, if a taxpayer does not comply with the mandatory disclosure requirements in respect of a transaction, a reassessment of the taxation year in respect of the transaction will never become statute-barred. This creates a considerable amount of uncertainty for taxpayers, as the CRA can reassess any number of years after a transaction if the disclosure requirements were not complied with.

The Proposals set out the following penalties for taxpayers (or persons who enter into a transaction for the benefit of the taxpayer) who do not meet the disclosure requirements with respect to reportable or notifiable transactions: (i) $500 per week for each failure to report a reportable or notifiable transaction, up to the greater of $25,000 and 25% of the tax benefit; or (ii) for corporations with assets having a carrying value of $50 million or higher, $2,000 per week, up to the greater of $100,000 and 25% of the tax benefit. For promoters or advisors who do not meet the disclosure requirements with respect to reportable or notifiable transactions, a penalty would be levied for each failure to report equal to the total of: (i) 100% of the fees charged; (ii) $10,000; and (iii) $1,000 for each day that they fail to report, up to a maximum of $100,000.

Corporations who fail to report uncertain tax treatments would be subject to a penalty for failure to report each uncertain tax treatment equal to $2,000 per week and up to a maximum of $100,000.

Avoidance of tax debts

Section 160 of the Tax Act is an anti-avoidance rule that is intended to prevent taxpayers from avoiding tax debts by transferring property to a non-arm’s length person for consideration that is less than the fair market value of the transferred property. The current rule applies when there is a transfer of property and, at the time of the transfer, the following criteria are met:

- the transferor is liable to pay tax under the Tax Act;

- the transferee is a person with whom the transferor is not dealing at arm’s length; and

- the fair market value of the transferred property exceeds the fair market value of the consideration given by the transferee for the property.

Where applicable, section 160 causes the transferee to be jointly and severally, or solidarily, liable for the transferor’s tax debts in respect of the taxation year in which the property is transferred or any preceding taxation year to the extent that the value of the transferred property exceeds the value of the consideration received by the transferor.

In Budget 2021, the Government stated that some taxpayers were engaging in complex transactions to circumvent section 160. In this regard, the Federal Court of Appeal and the Tax Court of Canada have recently rendered decisions in which the Government was unsuccessful in applying section 1603.

The Proposals introduce new anti-avoidance rules that broaden the application of section 160:

- Avoidance of non-arm’s length status: Proposed paragraph 160(5)(a) of the Tax Act is intended to address planning that avoids non-arm’s length status at the time of the transfer. The proposed rule deems a transferor and transferee to be dealing at non-arm’s length at all times in a transaction or series of transactions involving the transfer if:

- at any time during the period beginning immediately prior to the transaction or series of transactions and ending immediately after the transaction or series of transactions, the transferor and transferee do not deal at arm’s length; and

- it is reasonable to conclude that one of the purposes of undertaking or arranging the transaction or series of transactions is to avoid joint and several, or solidary, liability of the transferor and transferee for an amount payable under the Tax Act.

- Deferral of tax debts: Proposed paragraph 160(5)(b) of the Tax Act is intended to prevent taxpayers from deferring tax debts to a different taxation year than when the transfer occurs. The proposed rule deems a tax debt of the transferor to become payable in the taxation year in which the property is transferred if it is reasonable to conclude that one of the purposes for the transfer is to avoid the payment of a future tax debt by the transferor or transferee.

- Valuations: Proposed paragraph 160(5)(c) of the Tax Act is intended to determine the fair market value of the property transferred and the fair market value of the consideration transferred to the transferor based on the overall result of the series of transaction. In particular, the amount by which the fair market value of the transferred property exceeds the fair market value of the consideration given by the transferee is deemed to be the greater of the amount otherwise determined without reference to this proposed rule and the amount by which the fair market value of the property at the time of the transfer exceeds either:

- the lowest fair market value of the consideration (that is held by the transferor) given for the property at any time during the period beginning immediately prior to the transaction or series of transactions and ending immediately after the transaction or series of transactions; or

- if the consideration is in a form that is cancelled or extinguished during the period, nil.

- Transaction: Proposed subsection 160(0.1) of the Tax Act broadens the application of section 160 (and section 160.01 of the Tax Act as discussed below) by defining a “transaction” to include an arrangement or event.

The Proposals also introduce a third-party penalty pursuant to proposed section 160.01 for persons who engage in, participate in, assent to or acquiesce in “section 160 avoidance planning”. This new definition refers to planning activity, in respect of a transaction or series of transactions, by a person who knows (or would reasonably be expected to know but for circumstances amounting to culpable conduct), one of the main purposes of which is the reduction of a transferee’s joint and several, or solidary, liability for tax payable under the Tax Act (or would be so payable if not for a “tax attribute transaction”). The penalty is equal to the lesser of:

- 50% of the amount payable under the Tax Act that was sought to be avoided; and

- the total of $100,000 and the person’s fees in respect of the planning.

The Proposals include parallel amendments to the tax avoidance rules in section 325, and a parallel third-party penalty in section 325.03, of the ETA.

The proposed amendments to the Tax Act and ETA apply effective Budget Day.

Mutual fund trusts: allocations to redeemers by exchange traded funds

In the 2019 Canadian federal budget (Budget 2019), the Government proposed measures to limit the deduction of certain amounts allocated by a MFT to redeeming unitholders4, which were subsequently implemented and applicable to taxation years that began after March 18, 2019.

The current rules in the Tax Act that implemented the Budget 2019 measures generally apply to preclude a MFT from claiming a deduction in respect of the amount of any ordinary income allocated to a redeeming unitholder, as well as any taxable capital gains allocated to the redeeming unitholder, to the extent that the amount allocated exceeds the accrued capital gain on the redeeming unitholder’s units, as determined by a formula.

The Budget 2019 measures require a MFT to know the cost amount of the units held by a redeeming unitholder and whether the redeeming unitholder has an accrued capital gain on their units. In the case of an ETF (generally MFTs whose units are listed and in continuous distribution), the MFT will generally not have information regarding its unitholders or the cost amount of their units. Due to these concerns, the Government temporarily excluded the following MFTs from the application of the Budget 2019 measures:

- ETFs: a MFT where all of the units offered by the MFT in the taxation year are ETF Units, being units listed on a designated stock exchange in Canada and in continuous distribution; and

- Combined ETFs: a MFT that had a class or series of units that are ETF Units and another class or series of units that are non-ETF Units.

This temporary exclusion applied to taxation years that began before December 16, 2021 and has now expired.

The Proposals introduce new rules that will apply to limit the deduction of taxable capital gains allocated to redeeming unitholders by ETFs and Combined ETFs, instead of the current rules adopted pursuant to the Budget 2019 measures.

For ETFs, the new rules will apply to preclude an ETF from claiming a deduction to the extent that the total allocated amounts paid out of the ETF’s net taxable capital gains exceed a portion of those gains, as determined by a formula. Under the formula, an ETF’s deduction for taxable capital gains allocated to redeeming unitholders in a taxation year will be limited to an amount equal to the total net taxable capital gains of the ETF for the taxation year multiplied by a fraction:

- the numerator of which is equal to the lesser of:

- the total amount paid by the ETF for redemptions of ETF Units in the taxation year; and

- the greater of: (i) the net asset value of the ETF at the end of the taxation year; and (ii) the net asset value of the ETF at the end of the immediately preceding taxation year; and

- the denominator of which is equal to the sum of the net asset value of the ETF at the end of the taxation year and the amount determined for the numerator.

Conceptually, the formula intends to apportion the ETF’s net taxable capital gains between unitholders that redeemed their units in the year and the remaining unitholders and the new rules preclude the ETF from claiming a deduction for any over-allocation of taxable capital gains to the redeeming unitholders. Notably, in contrast to current rules, the deduction limitation is not based on the accrued gain on a redeeming unitholder’s units.

The Government Explanatory Notes accompanying the Proposals provide the following example of the application of the formula for ETFs:

A trust that is an ETF has a net asset value of $800 at the end of its current taxation year. The net asset value of the trust was $700 at the end of the immediately preceding taxation year. The trust disposed of assets during the taxation year resulting in net taxable capital gains for the year of $100. In the same taxation year, some beneficiaries of the trust redeemed their units and the trust paid a total of $500 to these beneficiaries on such redemptions. Using allocations to redeemers, the trust treats $200 of the $500 paid on redemptions as the total allocated amount, so that $100 is the portion of the total allocated amount that is paid out of the taxable capital gains of the trust.

In this example, the ETF’s deduction for taxable capital gains allocated to redeeming unitholders ($100) will be reduced by an amount equal to the total net taxable capital gains of the ETF for the year ($100) multiplied by an amount equal to the total redemption payments made in the year ($500) divided by the sum of total redemption payments made in the year plus the ETF’s year‐end net asset value ($500 + $800). Consequently, the ETF’s deduction for taxable capital gains allocated to redeeming unitholders ($100) will be reduced by $61.54 ($100 – ($100 × ($500 / [$500 + $800])), such that the ETF’s deduction will be limited to $38.46.

For Combined ETF’s, the Proposals introduce a hybrid approach under which a modified version of the formula for ETFs is applied in respect of redemptions of ETF Units and the current rules (subject to an additional limitation) are applied in respect of redemptions of non-ETF Units. At a high level, for redemptions of ETF Units, the formula for ETFs discussed above is modified to take into account only the portion of each of the net asset value and the net taxable capital gains of the Combined ETF that is referable to the ETF Units. For redemptions of non-ETF Units, the current rules apply, subject to the further limitation that the Combined ETF’s deduction for allocated amounts in respect of non-ETF Units cannot exceed the portion of the net taxable capital gains of the Combined ETF that is referable to the non-ETF Units as determined by a formula.

It should be noted that the Proposals do not apply to all MFTs with listed units. For example, MFTs, such as real estate investment trusts, whose units are listed on a designated stock exchange in Canada but are not in continuous distribution would not qualify under the new rules and will be subject to the existing rules.

The Proposals also amends a current rule (POD Reduction Rule) that automatically reduces a redeeming unitholder’s proceeds of disposition of redeemed units by the amount of any taxable capital gain realized by the trust on the in-kind transfer of property to satisfy the redemption. The Proposals amends the POD Reduction Rule so that it does not apply to MFTs. As a result of this amendment, the capital gains refund mechanism and the calculation of an MFT’s deduction for taxable capital gains allocated to redeeming unitholders will not be impacted by the POD Reduction Rule.

The foregoing amendments will apply for taxation years beginning after December 15, 2021.

Audit authorities

As described below, the Proposals expand the Minister’s audit powers by making parallel amendments to section 231.1 of the Tax Act and section 288 of the ETA. If passed, these proposals will come into force on Royal Assent.

(A) Proposed power to compel oral interviews

The Proposals authorize the Minister to require a “taxpayer or any other person” to attend an interview and answer proper questions orally, at a place chosen by the Minister or by video-conference or other form of electronic communication.

The Proposals would overrule a court decision issued in 2019, which held that section 231.1 of the Tax Act did not confer authority on the Minister to compel oral interviews.

If these Proposals are enacted, care should be taken in preparing employees of corporate taxpayers for interviews during corporate tax audits. The draft legislation is also silent on logistical issues that surround oral interviews.

(B) Proposed power to compel the format of written answers

The Proposals give the Minister authority to specify the form of written answers. For example, the Explanatory Notes accompanying the Proposals say that the Minister may require answers in the form of “an electronic spreadsheet or table” or “an organizational chart, or by another similar form of presentation”.

Prior caselaw has described limits on the Minister’s ability to compel a taxpayer, who has provided requested information on audit, to produce that same information again in another format, or to analyze the requested data when the Minister can do that analysis herself. The proposed amendments are not explicitly intended to overrule those authorities.

(C) Proposed scope of proper questions

The Proposals permit the Minister to require cooperation from a taxpayer when auditing “the obligations or entitlements of the taxpayer or any other person”.

Various bodies of law place limits on the Minister’s ability to further an audit of one taxpayer by asking a third party for information and documents. Examples include solicitor-client privilege and the statutory regime for audits of unnamed persons. The proposed amendments are not explicitly intended to overrule these other bodies of law.

(D) Proposed general audit power

The Proposals include a new provision saying that the Minister’s authorized persons may “require a taxpayer or any other person to give the authorized person all reasonable assistance with anything the authorized person is authorized to do” for any purpose related to the administration and enforcement of tax legislation.

The Explanatory Notes accompanying the Proposals provide no information about the purpose for this new, broad, general audit power.

Trust reporting

Under current rules, trusts are generally required to file an annual T3 return only if they earn income or make distributions in the year. Further to the announcement in Budget 2018, the Proposals contain rules relating to an enhanced regime of reporting requirements for trusts, as follows:

- trusts resident in Canada will be required to file a T3 trust income tax and information return every year; and

- trusts that are resident in Canada, as well as non-resident trusts that are required to file a T3 return, will also be subject to enhanced disclosure requirements, which include more personal information on trustees, beneficiaries or settlors, as well as information on who had the ability to exert control over trustee decisions.

Consistent with the Budget 2018 announcement, the Proposals list several exceptions to these new reporting requirements, including for MFTs, segregated funds and master trusts, trusts governed by registered plans, lawyers' general trust accounts, trusts that qualify as non-profit organizations and registered charities. The Proposals also create exceptions for: (i) trusts with less than $50,000 in assets throughout the taxation year, where the holdings are deposits, government debt obligations or listed securities; and (ii) trusts that have been in existence for less than three months.

The Proposals also contain the following additional changes in comparison to the original announcement in Budget 2018:

- the enhanced disclosure requirements are extended to so-called “bare trusts”, being arrangements under which a trust can reasonably be considered to act as agent for all the beneficiaries in respect to its dealings with the trust’s property;

- new exceptions to these disclosure requirements are added for: (i) trusts that have all of their trust units listed on a designated stock exchange; and (ii) information that is subject to solicitor-client privilege; and

- the implementation date for the new reporting requirements is deferred by one year and will apply for taxation years ending after December 30, 2022.

Measures not included in the Proposals

The Proposals to do include certain other significant measures announced or confirmed in Budget 2021, including rules relating to hybrid mismatch arrangements and consultations on Canada’s transfer pricing rules and modernizing the GAAR. For commentary on these measures, see our prior bulletin, “Highlights of Canada’s 2021 federal budget”.

- For commentary on this measure, see “Highlights of Canada’s 2019 federal budget”.