Indigenous involvement in major projects: 3 best practices to thrive in the evolving projects ecosystem

Authors

Michael J. Fortier

Michael J. Fortier

Brianne Paulin

At the same time as the role of ESG is rising in prominence across projects, Indigenous involvement in major projects across Canada continues to evolve and diversify. In addition to Indigenous groups sharing knowledge, and being engaged in and consulted on projects, Indigenous groups are increasingly acting as proponents, investors, or regulators of major projects.

As part of this evolution and diversification, Indigenous groups are increasingly playing multiple roles in major projects, including as regulators, proponents or investors. Such expanding Indigenous involvement in projects can have many benefits for both projects and their participants—including for project proponents continuing to refine their execution of projects in alignment with their broader ESG objectives.

This evolution also has the effect of increasing the complexity of the project ecosystem, which naturally raises the question for proponents (whether Indigenous or not) on how to thrive in this evolving ecosystem.

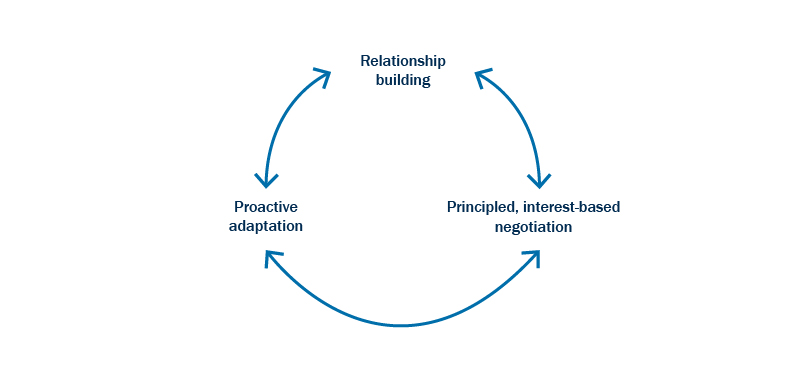

To thrive in Canada’s evolving ecosystem of Indigenous involvement in major projects, we have identified three key best practices:

- Genuine relationship building with a long-term view for at least the life cycle of the project or beyond;

- Principled, interest-based negotiation; and

- Proactive adaptation.

While seemingly simple in nature, these three best practices are often misunderstood and thus not implemented effectively—resulting in abandoned, rejected or sub-optimal major projects.

Genuine, long-term relationship building

Increasingly, proponents are seeking to develop relationships with Indigenous groups involved in a project, which is a good start. Unfortunately, the relationship building often stops at a superficial level and does not progress to a level that facilitates candid, meaningful two-way dialogue around needs, desires, constraints and goals.

As in any ecosystem, mutually beneficial relationships that continue to develop, grow and strengthen over time are key to the success and longevity of the project ecosystem and its participants. In contrast, a transactional, “box-checking” approach to relationships often fails at building durable bonds that can support a thriving project ecosystem.

Proponents of major projects need to think about their relationships with Indigenous groups as ongoing with a long-term view for the life cycle of the project and beyond. In other words, proponents need to develop, grow, and strengthen their relationship with Indigenous groups beyond the initial phase of interaction. A transactional approach, on the other hand, often requires repeated engagements between parties over time, increasing uncertainty.

Principled, interest-based negotiation

Principled, interest-based negotiation—i.e., negotiations focused on underlying reasons, values and motivations for each party’s position—is an increasingly important concept in this evolving ecosystem of Indigenous involvement in major projects for several reasons.

Principled, interest-based negotiations can be conducted:

- in a manner that enables relationships with Indigenous groups to develop and grow while also advancing reconciliation;

- in a multi-party/participant setting, which is increasingly becoming the reality (even if bi-lateral negotiations are occurring, there are likely multiple other negotiations occurring concurrently in the project ecosystem between the same or other parties);

- to align the participants’ interests in respect of developing, operating and decommissioning major projects; and

- to address the needs, desires, constraints and goals of each participant.

If conducted correctly, principled, interest-based negotiations can often increase the project’s ultimate performance, shorten project timelines and reduce the risk of disputes between project participants.

Given these potential benefits, principled, interest-based negotiation would be expected to be the norm. However, this negotiation approach is often not implemented fully or at all in practice due to: the unwillingness of project participants to sufficiently trust each other to engage in this way; the unwillingness to invest the time, effort and resources to implement such an approach; or a lack of knowledge or experience as to how to effectively implement this negotiation approach in the context of a major project.

While principled, interest-based negotiations will be context specific, some best practices can include: meeting early and often; providing sufficient information on the project; and having agreement on engagement procedure at various key stages of the project life cycle1. These negotiations also create opportunities to continuously build on the relationships between all the major project proponents.

Proactive adaptation

Given the complexity of developing a major project, unexpected changes are a reality. Project planning should include proactive adaptation measures to respond to this reality. A key part of being proactive is recognizing that unexpected changes will occur, and that these changes may necessitate adapting aspects of the project related to Indigenous involvement as well as the relationships between the project participants.

Two keys to effective and efficient proactive adaptation are having good relationships with Indigenous groups involved in the project and having previously, successfully used principled, interest-based negotiations; unexpected changes may often create conflict between project participants and a strong, resilient and effective relationship that engenders trust will enable participants to more effectively address unexpected change.

That said, even without a good relationship or past use of principled, interest-based negotiations, proactive adaptation can harness the power of principled, interest-based negotiation to help build relationships in the context of a dispute or a project that has veered off course. Although proactive adaption will likely require more time, resources and effort without good relationships and past experience using principled, interest-based negotiations, such use of proactive adaptation may be more beneficial than the alternatives, including litigation.

Each of the three best practices is important individually; the three of them together can often be transformative. The integration of these three best practices, among other things, fosters clarity and understanding that increases the likelihood of developing a project that advances reconciliation and that is viewed as—and is in fact—a socially acceptable and sustainable project.

- See Part IV of “Free, Prior and Informed Consent in Canada”: Towards a New Relationship with Indigenous Peoples”, paragraph 86.