Protecting Employees From and Responding to Cyber Bullying Employer Considerations

Authors

Introduction

The internet, and particularly social media, has expanded the frontiers of workplace bullying and harassment, bringing with it a host of issues for employers. This paper addresses legal issues related to cyber bullying in Canadian workplaces. We outline the varying definitions of cyber bullying and provide an overview of the evolving legal landscape as it relates to cyber bullying. We also review the case law relating to employer liability, and outline strategies for employers to protect employees from and to respond to cyber bullying.

Overview of Cyber Bullying and Harassment

Defining Cyber Bullying

As noted in the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights’ report titled “Cyberbullying Hurts: Respect for Rights in the Digital Age,” there is no commonly accepted definition for cyber bullying, and the lack of consensus on what it means creates significant challenges in understanding this phenomenon and taking steps to address it.1 The RCMP has defined cyber bullying as “the use of communication technologies such as the Internet, social networking sites, websites, email, text messaging and instant messaging to repeatedly intimidate or harass others.”2 Public Safety Canada has defined cyber bullying as “willful and repeated harm inflicted through the use of computers, cell phones, and other electronic devices.”3

The only legislation that provides a definition of “cyberbullying” in the Canadian context is the Intimate Images and Cyber-protection Act, S.N.S. 2017, c. 7 in section 3(c), although this legislation is not yet in force:

"cyberbullying" means an electronic communication, direct or indirect, that causes or is likely to cause harm to another individual’s health or well-being where the person responsible for the communication maliciously intended to cause harm to another individual’s health or well-being or was reckless with regard to the risk of harm to another individual’s health or well-being, and may include

- creating a web page, blog or profile in which the creator assumes the identity of another person,

- impersonating another person as the author of content or a message,

- disclosure of sensitive personal facts or breach of confidence,

- threats, intimidation or menacing conduct,

- communications that are grossly offensive, indecent, or obscene,

- communications that are harassment,

- making a false allegation,

- communications that incite or encourage another person to commit suicide,

- communications that denigrate another person because of any prohibited ground of discrimination listed in Section 5 of the Human Rights Act, or

- communications that incite or encourage another person to do any of the foregoing.4

Prevalence of Cyber Bullying in the Workplace

Bullying in the workplace is not a new phenomenon. In 1999, the International Labour Organization declared workplace harassment and violence one of the most serious problems facing the workforce in the new millennium. At the time, 75% surveyed said they were bullied at work.5According to a 2014 nationwide survey, 45% of Canadian workers report being bullied on the job.6

The explosive growth of social media technologies and the use of internet and mobile tools has provided additional mechanisms through which bullies can target their victims.7 “Work” is no longer a compartmentalized part of life, with distinct boundaries in terms of time and location—the boundaries have blurred, which serves “to modify the understanding that employees and employers have of civility, bullying and the limits of their corresponding rights and obligations, particularly in relation to online communication.”8

Cyber bullying in particular is commonly misperceived as affecting only adolescents. However, recent academic literature and media attention has focused on cyber bullying among colleagues at work. In 2006, a report revealed that 40% of Canadian workers experienced bullying on a weekly basis, and 7% of internet users in Canada aged 18 years or older self-reported having been a victim of cyber bullying.9 A 2014 Pew Research Centre study showed 40% of adult internet users have personally experienced online harassment, ranging from name-calling and embarrassment to physical threats, stalking and sexual harassment. 10 Further, an increase in the number of arbitration cases dealing with instances of cyber bullying demonstrates that the problem is spilling over into the workplace and the number of cases will likely increase.11Some studies indicate that the prevalence of cyber bullying varies depending on industry and organization.12

Deborah Hudson notes in her article “Workplace Bullying and Harassment: Costly Conduct” that although “it is difficult to determine exactly how much harassment and bullying actually occurs in Canadian workplaces, we can be certain of the impact of such conduct. Workplace bullying and harassment create a toxic work environment resulting in many negative effects which may include: decreasing productivity, increasing employees’ use of sick days, damaging employee morale and causing attrition of good employees.”13 The Canada Safety Council estimates that bullied employees spend 10-52% of their time networking for support and that chronic unresolved workplace conflict is a decisive factor in 50% of employee departures.14 Cyber bullying can also be costly: employee absence due to workplace bullying and harassment is estimated to cost $19 billion per year.15

Relevant Canadian Law

Aside from the Intimate Images and Cyber-protection Act, S.N.S. 2017, c. 7, discussed above, there are other statutory provisions across Canada that attempt to address bullying and harassment in the workplace. The main source of protection comes in the form of provincial occupational health and safety legislation. While certain instances of cyber bullying and harassment are addressed through provincial human rights codes, these human rights bodies are restricted to dealing with harassment on the basis of one of the prohibited grounds (such as race, religion, sex, disability, etc.).

Provincial occupational health and safety legislation has required that employers maintain a safe workplace, and in recent years, this legislation has undergone changes aimed at providing specific protections from workplace violence and harassment. For example, in 2010, Bill 168 amended Ontario’s Occupational Health and Safety Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. O.1 (the OHSA) by adding provisions requiring an employer to: prepare policies with respect to workplace violence and workplace harassment and to review these policies at least annually; develop a program to implement the workplace violence policy, with included measures to control risks of workplace violence, to summon immediate assistance when workplace violence occurs, and for workers to report incidents of workplace violence; and provide workers with information and instruction on the contents of the workplace violence policy and program.16 Under the OHSA, an employer that fails to comply with any provision under the Act is guilty of an offence and on conviction is liable to a fine of up to $100,000 or to imprisonment for up to 12 months, or to both.17 Furthermore, an employer is liable for any act or neglect of managers, agents, representatives, officers, directors or supervisors under its employ.18 More recently, WorkSafeBC implemented three Occupational Health and Safety policies effective March 2013, which explain the duties of employers, workers, and supervisors to prevent and address workplace bullying and harassment.19 With the exception of Yukon and New Brunswick, every jurisdiction in Canada has specific workplace violence prevention legislation.20

In addition to provincial legislative efforts, it is important for both employers and employees to know that there are Criminal Code provisions that can be used to penalize online bullies.21 In terms of harassment, all those found guilty of (a) repeatedly following from place to place the other person or anyone known to them; (b) repeatedly communicating, either directly or indirectly, with the other person or anyone known to them; (c) watching the dwelling-house, or place where the other person, or anyone known to them, resides, works, carries on business or happens to be; or (d) engaging in threatening conduct directed at the other person or any member of their family are subject to an indictable offence of less than ten years of imprisonment or a summary conviction.22 Further, those found guilty of knowingly publishing, distributing, transmitting, selling, making available or advertising an intimate image of a person knowing that the person depicted in the image did not give their consent, or being reckless as to whether consent was given, may, in addition to a sentence, be prohibited from using the internet or any other digital network or be restricted in accordance with conditions set by the court.23 What might be perceived as a harmless prank on a co-worker can have severe consequences, including a criminal record.

Employer Liability

Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace, Generally

In addition to the negative impacts on productivity and costs discussed above, there is the potential for an employer to be held legally liable for workplace bullying and harassment.

Employer liability for workplace bullying and harassment can attach even if there are policies in place, but where they are not actively enforced. For example, in Boucher v. Wal-Mart Canada Corp., 2014 ONCA 419, the court found that a former Walmart employee was harassed in the course of her employment by her manager and that Walmart had failed to address her complaints, and thus awarded her significant damages. The Superior Court jury awarded the former employee $200,000 in aggravated damages and $1,000,000 in punitive damages as against Walmart. Walmart appealed, and the Ontario Court of Appeal reduced the punitive damage award to $100,000. This case serves as a strong indication of how the courts treat employers that fail to take allegations of bullying and harassment seriously.

Furthermore, if the bullying or harassment escalates to the point where a victim feels compelled to quit, that individual could sue an employer for constructive dismissal. For example, in Shah v. Xerox Canada Ltd., 2000 CarswellOnt 831, the Ontario Court of Appeal found that Xerox’s treatment of the plaintiff made his continued employment intolerable, and therefore amounted to an unjustified repudiation of the employment relationship. As such, the plaintiff had been constructively dismissed, and was entitled to damages in lieu of the notice he should have received. The lower court also noted that while this was not the case for punitive damages, had the workplace bullying involved sufficiently callous, flagrant or outrageous disregard of the plaintiff’s rights, then that would meet the threshold required for punitive damages.24 A similar situation occurred in Morgan v. Chukel Enterprises Ltd., 2000 BCSC 1163, where the court deemed that the plaintiff was constructively dismissed as a result of the owners’ abusive behavior, and she was entitled to 13 months’ pay in lieu of notice. Given that the cases summarized above came before the legislative changes to occupational health and safety statutes which incorporated protections against workplace bullying and harassment, the damages analysis did not consider potential damages stemming from the employer’s failure to comply with legislative standards.

Cyber Bullying and Harassment, Specifically

Case law involving cyber bullying and online harassment in Canada is rare. The jurisprudence to date often involves disgruntled employees disparaging their employers’ reputations through online postings (i.e., “cybordination”).25

However, an employer can still be held vicariously liable for violations of the OHRC or other human rights legislation. For instance, the Ontario Human Rights Code, R.S.O. 1990, c H.19 (the Code) explicitly provides that an employer is vicariously liable for discrimination committed by an employee.26 This likely applies even if the discrimination occurs on an online forum. In Perez-Moreno v. Kulczycki, 2013 HRTO 1074, the Human Rights Tribunal found that comments made by an employee about a co-worker on Facebook constituted harassment in employment contrary to s. 5(2) of the Code. The employer was not a party to the complaint, but was nonetheless encouraged to consider whether human rights training might benefit all of its employees.27 Had the employer been named as a respondent to the complaint, there is certainly the possibility that the employer may have been found vicariously liable for the employee’s harassment.

Furthermore, employers may violate s. 5(1) of the Code by failing to appropriately respond to or prevent harassment (including online), thereby contributing to a “poisoned work environment.”28 In Taylor-Baptiste v. Ontario Public Service Employees Union, 2012 HRTO 1393, a manager of the Toronto Jail alleged that the Ontario Public Service Employees Union (OPSEU) and an employee and President of the Jail’s OPSEU local discriminated against her through comments posted on a blog. The comments contained sexist stereotypes and identified her family status. The issue was whether the blog posts violated s. 5 of the Code and in what circumstances statements made outside work hours, online, were considered “with respect to employment” or “in the workplace.” While the Adjudicator determined that this was not a case where the blog comments could be considered “in the workplace” under s. 5(2), the Adjudicator did leave room for the possibility that postings on blogs and other electronic media may be part of or an extension of the workplace and that the Code may apply to them. As such, employers may be liable for failing to ensure that there is not a poisoned work environment in the context of online harassment.

These employer obligations are not confined to the human rights context. A recent arbitral decision upheld a labour grievance against the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) for failing to stop and appropriately address abusive tweets targeted at employees on the Commission’s customer service account. The arbitrator found that the duty to protect employees from workplace bullying and harassment under human rights and occupational health and safety laws includes not just the physical facility but the social media sites an employer operates.29 The arbitrator found that, by providing information to employees on how to file a complaint, the TTC effectively acknowledged the abusive customer complaints. Further, it failed to take all reasonable and practicable measures to protect its workers from harassment through the Twitter account. This case illustrates that human rights and occupational health and safety laws, which are designed to protect employees from bullying and harassment, are sufficiently broad as to capture online conduct.

Strategies for Defending Claims

The best way for an employer to ensure that the workplace protects employees from cyber bullying and harassment is to have effective policies and programs in place, and to respond promptly and effectively to any complaints of cyber bullying.

Have Essential Policies and Programs in Place

In order to prevent cyber bullying in the workplace, employers should implement appropriate policies and procedures. Below, we discuss (a) workplace violence, bullying and harassment policies, (b) cyber bullying policies, (c) e-mail and internet monitoring policies and (d) social media usage policies.

Workplace Violence, Bullying and Harassment Policies. Employers should prepare clear policies that specifically address workplace violence, bullying and harassment.30 The policies should:

- clearly state that the organization will not tolerate workplace violence, bullying or harassment and is committed to preventing it;

- ensure the policy is clear that the “workplace” is not limited to the physical office, and may include posts on social media in appropriate circumstances;

- include clear examples of unacceptable behaviour (rather than abstract concepts);

- outline the roles and responsibilities of all workplace parties (management, employees, etc.) in preventing and reporting workplace bullying and harassment;

- set out a clear procedure for reporting, investigating and resolving complaints, both formally and informally; and

- set out disciplinary measures that may be used in the event of a breach of the policy.

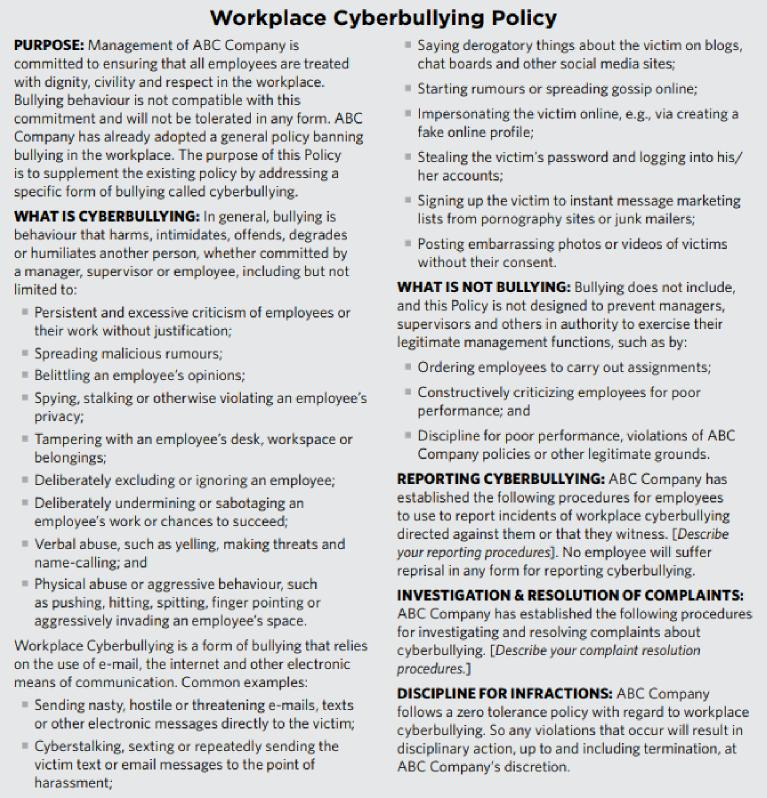

Cyber Bullying Policies. Employers may also consider developing a specific cyber bullying policy (or incorporating provisions relating to cyber bullying into the general workplace bullying and harassment policy). The HR Insider provided the following Model Policy as a starting point for policy specifically addressing cyber bullying in the workplace: 31

E-mail and Internet Monitoring Policies. Employers should consider developing policies which reserve their right to monitor communications over company-issued devices or over company servers, and which inform employees of their policies on internet, e-mail and telephone use, particularly if employees are subject to random or continuous surveillance.32 These policies should clearly indicate the right to monitor online use in the workplace. Although employees are entitled to privacy in the workplace,33 workplace policies and practices may diminish an individual’s reasonable expectation of privacy in a work computer or electronic device.34

Social Media Usage Policies.Another preventative step employers can take is to have social networking policies in place. While many employers have guidelines and codes of conduct for e-mail and internet use, social networking sites pose different challenges which may warrant special consideration.35 The policy should establish best practices and outline expectations for acceptable use of social networking sites in the workplace (broadly defined), and should set out consequences of misuse. The policy should also address any workplace privacy concerns (including whether the organization allows the use of social networking sites in the workplace, in what context and for what purposes, and whether the employer monitors these sites and the employee use).36

Enforcement of Workplace Policies

It is not enough to simply have policies and programs in place to prevent cyber bullying and harassment. A necessary component of effective policies and programs is that they are fully enforced and endorsed by all levels of management. As the Walmart case above illustrates, employers must develop and maintain a program to implement the various policies in order to ensure that employees are truly protected.

In order to ensure workplace policies are properly enforced, employers should consider:

- training employees on any relevant policies, both as part of onboarding and at regular intervals;

- ensuring management sets a strong “tone from the top” on issues of workplace bullying and harassment;

- being proactive in addressing issues of workplace bullying and harassment, rather than waiting for a complaint to be made;

- taking breaches of policies seriously, including by taking disciplinary action;

- supporting employees through all aspects of the relevant policies (including encouraging employees to report misconduct);

- retaining independent investigators to investigate complaints of workplace harassment or bullying, as appropriate;

- providing support to employees who have experienced workplace bullying or harassment, including online; and

- monitoring workplace use of the internet and company devices/networks, including random or targeted searches (being as minimally invasive as possible and ensuring the method of monitoring chosen is related to the purpose of the search).

Conclusion

Failing to protect employees from being cyber bullied or harassed potentially could expose organizations to liability under occupational health and safety, human rights and other laws. It is essential that organizations implement and enforce policies protecting employees from all forms of bullying and harassment, but particularly—given the increased online element in the workplace—from cyber bullying and harassment. This will not only limit employer liability and protect employees, it will reach the real goal of creating a productive and safe work environment.

This article originally appeared in alongside the OBA Annual Update on Human Rights CLE Program.

_________________________

1 Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights, “Cyberbullying Hurts: Respect for Rights in the Digital Age” (December 2012), available online at: http://sencanada.ca/Content/SEN/Committee/411/ridr/rep/rep09dec12-e.pdf

2 Royal Canadian Mounted Police, “Bullying and Cyberbullying”, available online at: www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/cycp-cpcj/bull-inti/index-eng.htm.

3 Public Safety Canada, “Info Sheet: Cyberbullying”, available online at: www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/2015-r038/index-en.aspx, citing Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2015), Bullying Beyond the Schoolyard: Preventing and Responding to Cyberbullying (2nd Ed) (Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin) and Patchin, J. W. (2014). What is cyberbullying? Retrieved from: http://cyberbullying.us/what-is-cyberbullying/.

4 A previous definition of cyber bullying from Nova Scotia’s former Cyber-safety Act, S.N.S. 2013, c. 2 was struck down in Crouch v. Snell, 2015 NSSC 340, where the court explicitly took issue with the Act’s definition of “cyberbullying”. The court noted that the statutory definition of cyber bullying included conduct where harm was not intended, but ought reasonably to have been expected (unlike malice). Thus, the statutory definition (along with other aspects of the statute) infringed on ss. 2(b) and 7 of the Charter and these violations were not saved by s. 1, and the court struck down the Act in its entirety.

5 See: University of New Brunswick, “Towards a Respectful Workplace”, available online at: www2.unb.ca/towardarespectfulworkplace/faqs.html; CBC News, “40% of Canadian bullied at work, expert says” (December 6, 2011), available online at: www.cbc.ca/news/canada/windsor/40-of-canadians-bullied-at-work-expert-says-1.987450.

6 Workers Health & Safety Centre, “Almost half of Canadian workers feel bullied on the job” (April 1, 2015), available online at: www.whsc.on.ca/What-s-new/News-Archive/Almost-half-of-Canadian-workers-feel-bullied-on-th.

7 Bettina West, et al., “Cyberbullying at Work: In Search of Effective Guidance”, Laws (2014) at p. 599.

8 Ibid.

9 Canadian Institutes of Health Research, “Canadian Bullying Statistics” (2012), available online at: www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/45838.html#7, citing Lee R.T., and Brotheridge C.M., “When prey turns predatory: Workplace bullying as predictor of counteragression/bullying, coping, and well-being”, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology (2006).

10 Pew Research Center, “Online Harassment” (October 22, 2014), available online at: www.pewinternet.org/2014/10/22/online-harassment/.

Bettina West, et al., “Cyberbullying at Work: In Search of Effective Guidance”, Laws (2014) at p. 601.11 See: Melanie Warner, “Criminal codes now allow for workplace cyber-bullies to be penalized”, Financial Post (April 28, 2015), available online at: business.financialpost.com/executive/management-hr/criminal-codes-now-allow-for-workplace-cyber-bullies-to-be-penalized.

12Bettina West, et al., “Cyberbullying at Work: In Search of Effective Guidance”, Laws (2014) at p. 601.

13 Deborah Hudson, “Workplace Bullying and Harassment: Costly Conduct”(Queen’s University Industrial Relations Centre: 2015), available online at: irc.queensu.ca/sites/default/files/articles/workplace-bullying-and-harassment-costly-conduct-by-deborah-hudson.pdf.

14 Government of Alberta, “What You Need to Know About Bullying in the Workplace”, available online at: alis.alberta.ca/tools-and-resources/resources-for-employers/what-you-need-to-know-about-bullying-in-the-workplace/.

15 Mental Health Commission of Canada, “Understanding, Managing and Preventing Workplace Bullying by Donna Marshall” (February 24, 2016), available online at: www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/february_workplace_webinar.pdf

16 Occupational Health and Safety Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. O.1, ss. 32.0.1-6.

17 Occupational Health and Safety Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. O.1, s. 66(1).

18 Occupational Health and Safety Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. O.1, s. 66(4).

19 WorkSafeBC, “BOD Decision – 2013/03/20-03 – Employer Duties – Workplace Bullying and Harassment” (March 20, 2013), available online at: www.worksafebc.com/en/resources/law-policy/board-of-directors-decisions/bod-2013-03-20-occupational-health-and-safety-workplace-bullying-and-harassment-policies?lang=en.

20 Alberta: Occupational Health and Safety Act, R.S.A. 2000, c. O-2.1; British Columbia: Occupational Health and Safety Regulation, B.C. Reg. 296/97; Manitoba: Workplace Safety and Health Regulation, Man. Reg. 217/2006; Newfoundland & Labrador: Occupational Health and Safety Regulations, 2012, N.L.R. 5/12; Northwest Territories: Occupational Health and Safety Regulations, N.W.T. Reg. 039-2015; Nova Scotia: Violence in the Workplace Regulations, N.S. Reg. 209/2007; Nunavut: Occupational Health and Safety Regulations, Nu Reg. 003-2016; Ontario: ,Occupational Health and Safety Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. O.1; Prince Edward Island: Occupational Health and Safety Act General Regulations, P.E.I. Reg. EC180/87; Quebec: Act respecting labour standards C.Q.L.R. c. N-1.1; Saskatchewan: The Occupational Health and Safety Regulations, 1996, R.R.S. c. O-1.1 Reg. 1.

21 Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, ss. 162.1-162.2, 264(1-4). See also provincial legislation which creates a private cause of action for victims of non-consensual disclosure of intimate images: Alberta: Protecting Victims of Non-Consensual Distribution of Intimate Images Act, S.A. 2017, c. P-26.9, s. 3; Manitoba: The Intimate Image Protection Act, C.C.S.M., c. 187, s. 11; Nova Scotia: Intimate Images and Cyber-protection Act, S.N.S. 2017, c. 7, s. 5; Saskatchewan: Bill 72, An Act to amend the Privacy Act, 2nd Sess., 28th Leg., Saskatchewan, 2017, cl. 5 (third reading 28 March 2018).

22 Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, s. 264(1-4).

23 Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, s. 162.2(1).

24 Shah v. Xerox Canada Ltd., 1998 CarswellOnt 4130 at para. 42.

25 See, for example: Chatham-Kent (Municipality) v. National Automobile, Aerospace, Transportation and General Workers Union of Canada (CAW-Canada), Local 127 (Clarke Grievance), [2007] OLAA No. 135 at para. 25; Alberta v. Alberta Union of Public Employees (Re R), [2008] AGAA No. 20, varied in Alberta v. Alberta Union of Public Employees (R Grievance), [2011] AGAA No. 58; West Coast Mazda (Lougheed Imports Ltd. (c.o.b. West Coast Mazda) (re), 2010 BCLRBD No. 1980. See also: Denis Ellickson and Meg Atkinson, “Social Media and Workplace Discipline: Bringing Employee Free Speech and Reasonable Expectations of Privacy into the Analysis”, Ontario Bar Association, Volume 13, No. 4 (June 2012), available online at: www.oba.org/en/pdf/sec_news_lab_jun12_social.pdf.

26 Section 46.3.

27 At para. 17.

28 Taylor-Baptiste v. Ontario Public Service Employees Union, 2012 HRTO 1393 at para. 27. See also: Ontario Human Rights Commission v. Farris, 2012 ONSC 3876 (Div. Ct.) at paras. 29-36.

29 Amalgamated Transit Union, Local 113 v. Toronto Transit Commission (Use of Social Media Grievance), [2016] O.L.A.A. No. 267.

30 Provincial statutes largely require employers to have workplace violence and harassment policies.

31 HR Insider, “Workplace Bullying and Cyberbulling: The Employer’s Liability Risks” (March 2017), available online at: https://hrinsider.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/HRI_Mar_2017_WEB.pdf.

32 Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, “Privacy in the Workplace” (April 2004), available online at: www.priv.gc.ca/en/privacy-topics/privacy-at-work/02_05_d_17/

33 See, for example, Puretex Knitting Co. v. C.T.C.U., 23 L.A.C. (2d) 14 and La-Z-Boy Canada Ltd. v. C.W.A., Local 80400, 143 L.A.C. (4th) 88.

34 Ibid at para. 3.

35 Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, “Privacy and Social Networking in the Workplace”, updated December 2015, available online at: https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/privacy-topics/privacy-at-work/02_05_d_41_sn/; Jennifer Bond and George Waggott, “Social Media Policies in the Workplace: What Works Best?” (The Canadian Bar Association: September 24, 2014), available online at: https://www.cba.org/Publications-Resources/CBA-Practice-Link/2015/2014/Social-media-policies-in-the-workplace-What-works.

36 Ibid.