In the Terms: Canadian Private Equity Financings and U.S. Debt Terms: What's Market?

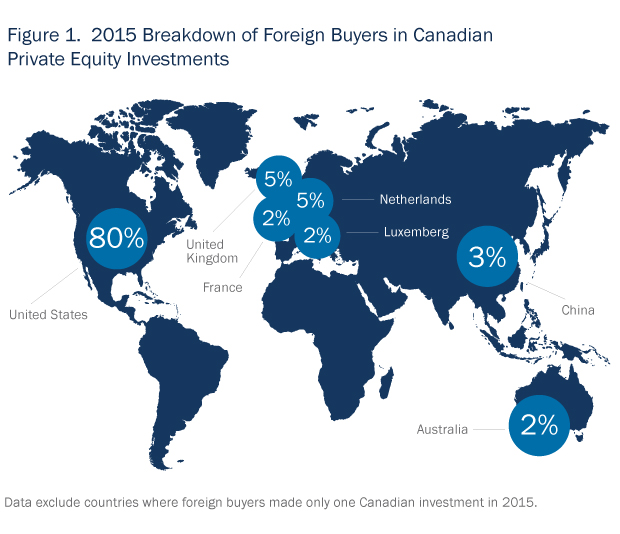

In 2015, foreign investors (largely U.S. based—see Figure 1), accounted for nearly half of private equity investment activity in Canada,1 and favourable market conditions are expected to draw more U.S. investment to Canada in the year ahead. U.S. sponsors investing in Canada may bring their U.S. debt financing sources north with them (which will come with potential hurdles)—or rely on Canadian bank financing. To the extent they use Canadian bank loans, U.S. sponsors may need to adjust their expectations as to what’s market in private equity debt terms in Canada.

Covenant lite loans

Leveraged loans traditionally contain financial maintenance and restrictive covenants to protect lenders from the increased risk that comes with higher-leverage multiples. In larger U.S. markets, “covenant lite loans” without any financial maintenance covenants have become common, initially in larger deals but increasingly in middle market deals.

By eliminating the risk of a default due solely to declining revenue, these loans give sponsors greater flexibility. While borrowers are still subject to negative covenant restrictions (such as those restricting debt incurrence, liens, asset sales and investments) in covenant lite loans, a portfolio company can only breach these covenants by actively engaging in a prohibited transaction.

In contrast to the U.S., covenant lite loans are not yet available in the Canadian market. The combination of the small size of the loan market, the nature of risk assessment and the more conservative nature of banks in Canada reduce the likelihood that covenant lite loans will be an option available to leveraged borrowers in Canada in the near term.

Equity cures

U.S. equity cures—which allow the sponsor to contribute additional equity (treated as EBITDA) to the portfolio company borrower in order to comply with financial maintenance covenants—are generally subject to limits on the number of cures over the loan term (and for consecutive fiscal quarters in middle market loans), dollar caps, and requirements that the equity proceeds be applied to prepay loans.

While not yet entirely accepted in the syndicated Canadian loan market, equity cure provisions are seeing more use in Canadian bank private equity financing deals with similar restrictions to those found in the U.S. middle market.

Net leverage ratio

In U.S. loans with financial maintenance covenants, it has become typical to calculate the leverage ratio (debt to EBITDA) or secured leverage ratio (secured debt to EBITDA) net of unrestricted cash on hand (up to a negotiated cap, in the case of middle market loans).

In Canada, whether the leverage ratio will be calculated net of cash on hand is still a matter of negotiation, though we are seeing this more frequently in PE-sponsored deals.

Incremental loans

In the U.S., the size of the uncommitted incremental facility is increasingly governed by a fixed amount available to the borrower regardless of the level of the secured leverage ratio, and a further unlimited amount if secured leverage ratio levels are satisfied. If the EBITDA of a borrower increases, the size of its available incremental facility will also increase. Similarly, if EBITDA is constant and debt is repaid over time, sponsors have flexibility to lever a portfolio company back up to closing levels. Such additional debt capacity has often been used to pay sponsors dividends.

In Canada, an incremental facility will most often have a fixed maximum amount. Canadian banks generally look for a borrower to de-lever over time, and so to the extent that EBITDA increases or debt is repaid, banks will want the benefit of a stronger borrower and a lower risk profile rather than allow the borrower to increase leverage back up to closing levels.

Loan buybacks

During and following the ‘08 financial crisis, many U.S. loans traded well below par, and borrowers and PE sponsors sought to purchase their debt at a discount. It has become relatively common in the U.S. to permit a borrower and its affiliates to offer to repurchase loans as long as the offers are made pro rata to all lenders and there is no requirement for any lender to sell. Loans purchased by a borrower must be cancelled upon purchase, whereas loans purchased by an affiliate of the borrower are not cancelled and the affiliate will be a lender going forward, subject to limitations on voting rights.

Loan buyback provisions are not common in the Canadian market and given the small size of the secondary market in Canada, are unlikely to have the same benefit to borrowers in Canada as in the U.S.

What gives?

Why have U.S. loan practices had limited success in Canada? One obvious answer is simply that the U.S. loan market is larger and as more lenders compete for attractive deals, sponsors are able to negotiate more favourable terms than in a smaller market.

Another is the makeup of the lender groups and the secondary market. In Canada, leveraged loans have traditionally been advanced and held by the Big Six banks until maturity or sold to similar institutions on the secondary market. In the U.S., much of the debt used to finance private equity acquisitions comes from institutional lenders rather than the bank market. Non-bank lenders have become the primary debt funding source for U.S. middle market leveraged buyouts and are increasingly active on larger U.S. deals as well.

Even when a traditional U.S. bank structures and underwrites a deal, it will typically seek to sell most if not all of its term loans to institutional investors. The focus of the underwriting bank is on the protections required to sell the loan in the current market rather than the long-term credit view taken by Canadian banks.

Using U.S. debt to fund a Canadian acquisition

With few tax or regulatory restrictions on Canadian borrowers tapping into the U.S. debt markets, U.S. debt capital sources can help fund a Canadian acquisition. One practical hurdle has been the need to develop an FX hedging strategy since a Canadian borrower’s revenue will be in Canadian dollars while its debt service will be due in U.S. dollars. These hedges can be costly and are generally only provided by traditional banks and affiliates, limiting the involvement from some of the more attractive U.S. non-bank funding sources.

However, these practical hurdles may be overcome; for example, Torys recently acted for a Canadian portfolio company borrower in a Canadian dollar loan from a U.S. debt fund lender with U.S.-style loan documentation. If more U.S. institutional lenders opt to lend in Canadian dollars in the future, this may create additional options for Canadian borrowers. Otherwise, we expect that core differences between markets will largely require U.S. sponsors to continue to adapt to Canadian debt terms in 2016 when borrowing from Canadian banks.

_________________________

1 For a year-over-year review of Canadian deal's with a foreign buyer, see "In the Markets—Canadian Private Equity in 2015," Figure 4.