The M&A Clock is Ticking for SPACs in Canada

![]()

A special purpose acquisition company, or SPAC, is a publicly traded shell company created with the commitment to purchase an unidentified future target. Long popular in the United States, this novel way to finance an M&A transaction has broken ground in Canadian IPO markets.

So far, the Canadian variety is modelled closely after the U.S. SPAC, sharing a number of investor-friendly characteristics and among them, a defined timeline to source an acquisition. The future of SPACs in Canada—including the success that the country’s early adopters will have in investing approximately C$1 billion of raised capital—is a trend being followed closely by market participants.

How Does a SPAC Work?

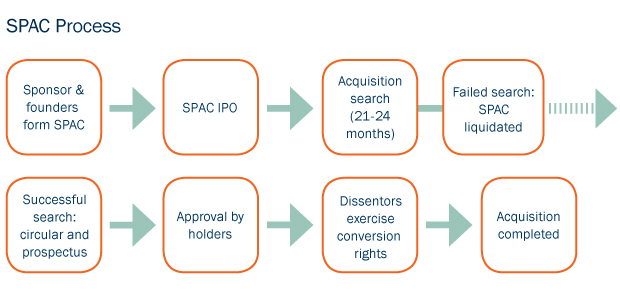

A SPAC is a shell that raises capital through an IPO to investors. IPO proceeds are placed in escrow to fund the future acquisition of one or several businesses or companies (a “qualifying acquisition”). At the IPO stage, the SPAC has no revenue, assets or operating history, but is backed by a sponsor and proven management team or founders with the relevant knowledge and contact base to source the prospective transaction. It is on the strength of the founders’ expertise that investors are willing to invest in a SPAC.

Units offered to investors typically comprise one share and a half purchase warrant exercisable at a premium to the IPO unit price following completion of the qualifying acquisition. If the acquisition is not completed by the set date—typically 21 to 24 months after the launch of the IPO—the SPAC is liquidated and escrowed proceeds are distributed to investors. The founders, who normally hold a 20% equity stake in the SPAC, cannot participate in the liquidation and lose their initial investment.

A qualifying acquisition cannot be completed without approval from investors by a majority vote. Under current practice, sponsors are entitled to vote their equity stake on a proposed acquisition, which facilitates meeting the shareholder approval requirement. Shareholders may also exercise conversion rights entitling them to receive their pro rata portion of the escrowed proceeds, regardless of whether and how such shareholders vote on the proposed acquisition. Current practice limits the exercise of these conversion rights by prohibiting a SPAC shareholder and its affiliates and joint actors from converting more than a total of 15% of the number of SPAC shares issued and outstanding following closing of the IPO.

Newer U.S. SPACs dispense with the shareholder approval requirement, thereby removing a degree of uncertainty; rather, shareholders are given the right to have their interest redeemed for cash without a shareholder vote (unless otherwise required by law or stock exchange rules). In addition, the JOBS Act has made it simpler and more cost-effective for SPACs to go public in the U.S. by reducing some public company reporting requirements.

Who Might be Interested in a SPAC?

SPACs are intended to provide an opportunity for the public to invest in companies that normally attract investment from private equity firms, with the benefit of significant investor protections, including the right for investors to vote on the qualifying acquisition, exercise their conversion rights described above or recover their pro rata portion of the escrowed fund if the SPAC fails to complete a deal within the specified timeline.

For target companies, the SPAC presents an alternative to a traditional IPO: the seller can cash out with the possibility of retaining an equity stake in a publicly traded vehicle that has immediate access to a strong and reputable board of directors and management team. As a listed shell company with no operating history, the SPAC also gives targets access to the capital markets in a process potentially less costly than undertaking a reverse takeover of an existing public company.

What Makes a SPAC Successful?

The key driver in a SPAC IPO’s success is the strength and credibility of the founders selecting the target acquisition. And unlike traditional PE funds that may have investment restrictions, the SPACs that have gone public to date generally permit their founders to focus on the target, geography and sector of their choice. However, as the Canadian SPAC market matures, we would expect to see SPACs with a more clearly defined sector or geographic focus.

Founders face a relatively short deadline to source a quality target in a competitive environment, seek shareholders’ majority approval (including preparing and filing an information circular and prospectus on the proposed acquisition) and consummate the transaction—and if they fail to meet the deadline, the founders must forfeit their investment in the SPAC. It may also be challenging for SPACs to compete in hot auctions where other prospective buyers may not be subject to similar restrictions.

Success also depends on the extent to which shareholders exercise their conversion rights. The withdrawal by some dissenting shareholders of their relevant portion of the escrowed proceeds in the face of a proposed acquisition has the ability to influence the amount of funds readily available to complete the transaction. This may require the SPAC to raise additional financing, adding another layer of complexity and timing to the process. While a proposed acquisition will also be conditioned on conversion rights not being exercised beyond a set threshold, uncertainty around shareholder response contributes to the overall risk profile of the SPAC.

Recent U.S. SPACs have introduced a number of workarounds to address conversion risk. For example, third parties and sponsor-related parties have made equity investments in the SPAC prior to completion of the acquisition, or committed to do so in the event of a capital shortfall. Proceeds have helped secure SPAC cash levels while also demonstrating investors’ backing of the proposed acquisition. SPACs have also raised capital through private placement offerings timed simultaneously with the acquisition closing.

The success of the SPAC in Canada will be measured in a few years’ time, when the race to beat the clock and complete a qualifying acquisition has been decided.

On the flipside, a successful SPAC has the potential to make significant gains for founders with a 20% stake (which they acquired for nominal value on the SPAC’s formation) in the post-acquisition vehicle, though U.S. practice shows that these sponsor promotes have been reduced as part of the agreement reached to complete a qualifying acquisition. It remains to be seen whether the size of sponsor promotes will equally decrease in Canada as the SPAC market here evolves.

SPACs in Canada so Far

Currently, the structure of the Canadian SPAC is largely influenced by the U.S. model described above. TSX rules require that SPACs complete a qualifying acquisition within 36 months of their IPO, though all recent Canadian SPACs have been structured to complete their acquisitions within a more competitive 21 to 24 months (unless shareholders and the TSX approve an extension to 36 months).

The Canadian SPAC IPOs launched this year have largely drawn interest from both Canadian and U.S. institutional investors, with the type of retail investors often seen investing in SPACs in the U.S. not yet forming a significant portion of the Canadian investor pool. The founders of these SPACs include some of Canada’s most experienced and successful business players, who are expected to extend their access to vast networks and potential acquisition opportunities to the SPACs they have helped found. Long term, the success of the SPAC in Canada hinges on whether the SPACs that have gone public will complete qualifying acquisitions within their tight timeframes.

Is the Canadian SPAC Here to Stay?

Like other IPOs, SPACs are subject to market conditions. Their emergence in Canada comes at a time when investors are looking for ways to commit their capital. Ultimately, players hoping to engage in a SPAC in Canada should view the opportunity not only alongside their broader assessments of the marketplace, but also with the understanding that a SPAC’s ultimate success will be measured in a few years’ time, when the race to beat the clock and complete a qualifying acquisition has been decided.