Shareholder Activism: More Settlements, Fewer Fights

Authors

Shareholder activism has been on the rise for several years and shows no sign of abating. As corporate Canada adapts to this new reality, we are seeing an evolution, both in activist tactics and in how boards respond to activist overtures.

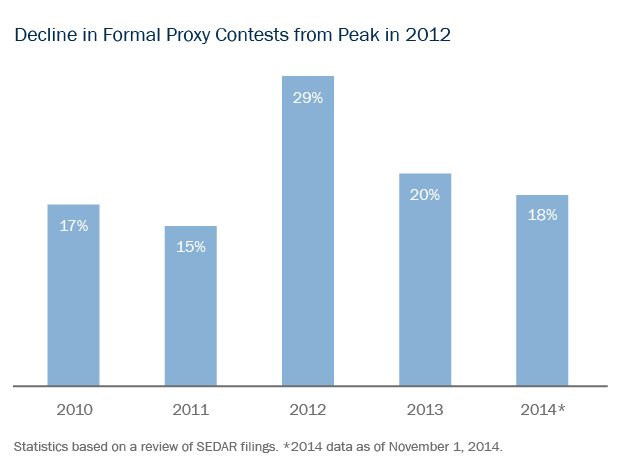

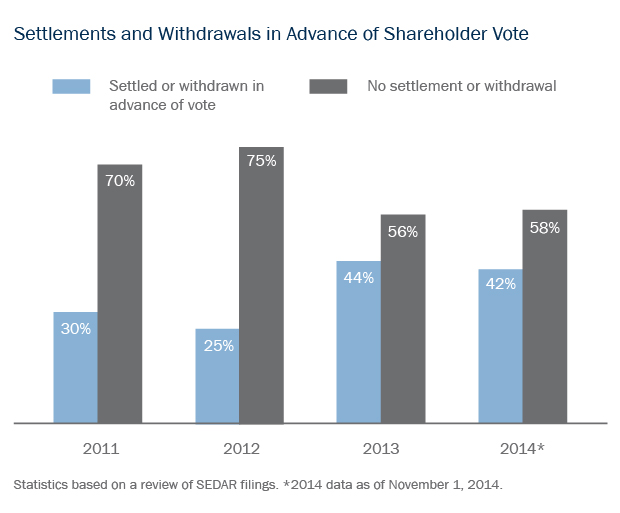

Activists are increasingly looking to achieve positive change through agreed measures short of a change of control, rather than by highly personalized “winner-take- all” campaigns. Likewise, incumbent boards are increasingly responding to activist overtures through dialogue with a view to finding common ground that addresses legitimate concerns, rather than with a reflexive defensive approach. This more nuanced approach is consistent with a board’s fiduciary obligations; it leads to a settlement where there is a reasonable settlement to be made; and it best positions the board for a successful defence to activist attack where a fight to the finish is warranted in the interests of the corporation. We think this trend will continue.

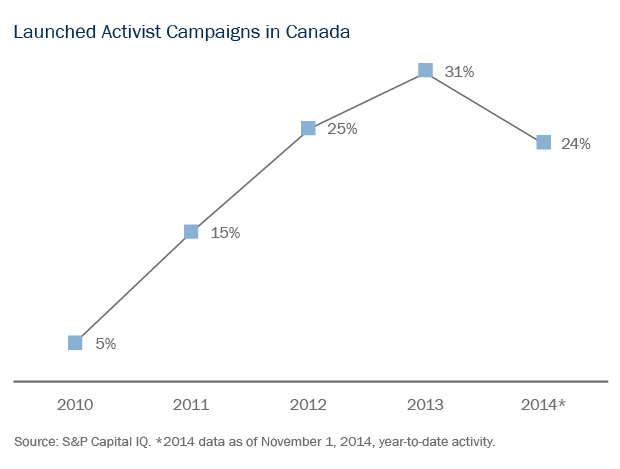

Shareholder activism, which started largely as a U.S. phenomenon, has only recently taken root in Canada. In the past, dissatisfied shareholders typically sold their shares rather than remaining invested and trying to change corporate management or strategy. Various explanations have been offered for this relative quiescence in Canada, including the cozier and more interconnected Canadian business community (as compared with the U.S.) and the “kinder and gentler” Canadian national character; but whatever the reason, things have changed.

Beginning in 2008, Canada experienced a significant increase in more aggressive shareholder action, largely as a result of hedge fund investors who had learned through U.S. experience that there was money to be made in actively advocating that investee companies change strategy—usually with a view to driving shareholder value in the near term—and seeking to replace management where necessary. Investors have also paid attention—capital inflows to activist hedge funds have been increasing steadily, as have returns in such funds.

Activist initiatives usually began with an aggressive overture to management that was followed by an equally aggressive letter outlining the many faults of the current management and demands for immediate and substantial change. In many cases what was demanded amounted to a change-of-control transaction. Failure to comply meant that a shareholders meeting would soon be requisitioned. Large companies with strong corporate governance practices have not been immune to such aggressive attacks, especially in the United States.

This form of shareholder activism still occurs and will likely continue, at least to some degree. However, what we are starting to see is a class of activists shifting away from highly personalized attacks that press for control transactions to an approach of seeking influence to effect change and increase share price through proposed operational initiatives or specific transactions. With more constructive activist overtures of this kind, the issue, as sophisticated boards and shareholders have come to realize, comes down to how best to increase shareholder value and over what timeframe. The challenge becomes convincing shareholders of who has the better plan—the activist or incumbent management?

One of the consequences of this evolution in activist tactics is an increased willingness of incumbent boards to engage with activists, potentially leading to negotiated settlement arrangements with one or more activist nominees going on the board and some or all of the activist’s business plan being adopted. With any such settlement, only time will tell whether the new board works well, and how the activist’s new influence will affect the company’s strategic direction in the long term. Activists have no fiduciary obligation to the company or to its other shareholders, and their investment horizons and incentive will drive behavior that is in their own interests. However, where their interests are aligned with those of the company and its other shareholders, the board may conclude that a settlement makes sense.

The attractions to both boards and activists of a negotiated settlement instead of going through full proxy fights are not hard to understand:

- An activist often makes proposals that drive shareholder value in the near term, which may be compelling to other shareholders (especially institutional shareholders with large stakes), making outright rejection hard for the board.

- In an increasing number of cases, the activist will have, at considerable effort and expense, performed diligence investigations, learned about the company’s business and developed a thoughtful thesis on how to improve value. This sort of analysis is difficult for a board to ignore, especially when it knows that the same information will be shared with the company’s major shareholders.

- The activist may already have the support of a number of the company’s major shareholders, effectively ruling out a “straight-arm” response that ignores the case being made.

- A fight to the finish is time-consuming, distracting and expensive, and involves considerable reputational risk for the incumbent board.

- Settlement arrangements provide the prospect, through a standstill covenant, of a period of stability that will allow the target company to return to focusing on its business. In addition, bringing the activist onto the board and adopting some or all of its business plan suggestions, invests the activist in the company’s new plan. In a successful settlement, this results in the opposing parties becoming aligned and focused on increasing shareholder value.

As the landscape of activism continues to change in Canada, we foresee increasingly sophisticated activist approaches and more nuanced board responses that recognize the potential for activists to play a constructive role in the company’s evolution.