Foreign Investors Will Change Their Investment Strategies to Compete for Canadian Oil and Gas Assets

As demand for commodities grows, particularly in Asia, we have witnessed an upsurge in foreign direct investment in Canada's oil and gas sectors. The involvement of state-owned enterprises in these investments is challenging the traditional parameters of Canada's foreign investment review regime. Recent policy updates and continued regulatory uncertainty will increasingly prompt foreign investors to modify their investment strategies. Foreign investors will adapt by varying the structures of their transactions, engaging proactively with key stakeholders and strengthening the terms and conditions of their merger agreements.

Foreign Investors Becoming More Assertive

Traditionally, investment in the Canadian oil and gas industry has been structured in the form of joint ventures or partnerships with Canadian counterparties, which have not triggered foreign investment reviews under the Investment Canada Act (ICA).

However, foreign entities have recently employed more assertive modes of investment, including outright acquisitions. For example, in 2012, CNOOC, one of China's largest and most prominent state-owned oil and gas companies, put forward a US$15.1 billion proposal to acquire all the shares of Nexen Inc. Also in 2012, Petroliam Nasional Berhad (Petronas), a Malaysian state-owned oil company, announced that it planned to acquire Progress Energy Resources Corp, its joint venture partner in certain Canadian shale gas assets, for approximately C$5.5 billion. This latter acquisition is the first example of an Asian company buying out its Canadian oil and gas joint venture partner through a direct takeover.

State-Owned Enterprises Becoming the New Buyers

The transactions mentioned above are notable not only for the method of acquisition but also for the changing face of the acquiror. While multinational corporations continue to execute takeovers in the Canadian energy industry, investments are increasingly being made by state-owned enterprises (SOEs). SOEs present unique considerations for the government in the application of the "net benefit test." They have also attracted attention from the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service (CSIS), which has warned of the potential national security risk that could be associated with investments by some SOEs. The rising incidence of SOE foreign investment and the expectation that it will grow in scope and magnitude continue to bring Canada's foreign investment review regime under scrutiny.

Addressing Regulatory Uncertainty on Investments into Canada

Uncertainty regarding the regulatory regime has arisen from recent foreign investment reviews under the ICA. The statutory net benefit test has been criticized for being vague and unclear. Popular concern about foreign ownership also continues to politicize high-profile transactions. Adding to the complexity are unexpected non-approvals, such as the government's stunning initial rejection of Petronas's application to acquire Progress Energy, and the continued role of provincial governments in the federal review process. Although both the CNOOC/ Nexen and Petronas/Progress transactions ultimately received ICA approval, uncertainty continues. For U.S. transactions, foreign investment reviews by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) can be fraught with similar issues. CNOOC/Nexen is undergoing a CFIUS review, and in early 2012, President Obama prohibited a Chinese-owned company from acquiring four wind farm project companies located within, or in the vicinity of, restricted air space at a U.S. Navy weapons systems training facility. Recent changes in Canada to clarify foreign investment rules emphasize the need for parties seeking to invest in Canada to adapt their investment strategies to fit within the existing Canadian regime.

Merger parties have primarily sought to respond to the current regulatory regime in two ways. First, they are structuring transactions to avoid a review or to minimize the risk of non-approval. Second, they are managing risk through provisions in their merger and acquisition agreements. We expect these trends to continue in 2013.

Shaping the Transaction to Avoid a Review

When Glencore agreed to acquire Viterra, it also entered into separate agreements to sell large parts of Viterra's Canadian operations to two Canadian businesses, Agrium and Richardson International. These undertakings allowed Glencore to adopt the position that the acquisition of the Canadian business was, in large part, not a foreign acquisition. Prime Minister Harper responded to the announcement of the transaction by saying, "My understanding of the deal is that many of the assets will actually remain in Canadian hands, so I'm not sure it really would be categorized at this point as primarily a foreign investment."

Similarly, we noted in our 2012 Top M&A Trends that merger parties should be prepared to offer significant, specifically tailored and creative undertakings to obtain approval, and we have seen this play out in 2012. For example, CNOOC agreed to pay a large premium for its proposed acquisition of Nexen and outlined plans to enter into generous net benefit undertakings. Although the large majority of Nexen's assets are outside Canada, CNOOC offered to establish Calgary as CNOOC's North and Central American headquarters, retain Nexen's management team and employees, and list its shares on the TSX.

Although the CNOOC/Nexen transaction was approved, in 2012 the tone of the government's attitude toward SOE acquisitions became sharper and more negative, particularly in connection with oil sands investments. As a result, SOE investment in the oil sands will now likely revert to focusing on minority stakes and joint venture arrangements not subject to review.

Although the CNOOC/Nexen transaction was approved, in 2012 the tone of the government's attitude toward SOE acquisitions became sharper and more negative, particularly in connection with oil sands investments. As a result, SOE investment in the oil sands will now likely revert to focusing on minority stakes and joint venture arrangements not subject to review.

Lowe's bid for Quebec-based Rona demonstrated that buyers that fail to modify their behaviour to minimize political and regulatory opposition do so at their peril. Lowe's made no meaningful attempt to address these potential risks and launched a hostile bid in the context of a provincial election. The Quebec government reacted negatively. It said it would use "all the means" it could muster to block the acquisition and floated the idea of establishing a buyout group to counter the bid. BHP's failed hostile bid for Potash has made clear that hostile transactions bear increased political risk.

In a friendly transaction, the target's support can help diffuse political opposition by emphasizing transaction benefits. Potash also demonstrated the political risk of launching a controversial takeover bid before an election. Provincial governments are now keenly aware of the role they can play in sensitive transactions and will not hesitate to get involved, particularly if there is popular concern over a takeover during an election campaign.

Seeking Support from Key Stakeholders

More generally, merger parties should plan to manage all key stakeholders in highprofile M&A transactions involving foreign buyers, particularly at the provincial level. As part of foreign investment reviews, the federal government seeks input from provinces. It will rarely or only hesitantly proceed without provincial government support. Provinces know this and are taking on an increasingly central role in reviews.

In the Glencore/Viterra transaction, the Saskatchewan government commissioned a report on the deal's "net benefit to Saskatchewan." Similarly Nexen is reported to have met with a variety of government agencies, including CSIS, prior to the announcement of its transaction with CNOOC. Government-relations advisers can play a key role in these efforts and need to be involved in the early stages.

Tailoring the Transaction Documents to Minimize Regulatory Risk

Merger parties are also managing risk through the terms of their M&A agreements. We are seeing increased use of so-called hell or high water clauses that outline the steps that buyers must take to obtain regulatory approvals. In the extreme, these covenants can require buyers to agree to any terms and conditions imposed by regulators as a condition of obtaining their approval. More commonly, these clauses contain caps or limitations to obligations that can potentially be imposed on buyers by the regulators. For example, buyers may be permitted not to accept terms and conditions that would have a material adverse effect on the acquired business. Parties may also agree to longer than ordinary outside dates to accommodate extended reviews and to make reverse break fee payments to targets in the event that a transaction does not proceed as a result of the failure to secure regulatory approvals.

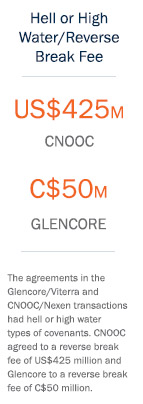

The agreements in the Glencore/Viterra and CNOOC/Nexen transactions had hell or high water types of covenants. CNOOC agreed to a reverse break fee of US$425 million and Glencore to a reverse break fee of C$50 million. In some cases, particularly in multijurisdictional transactions, deal terms may impose different obligations on buyers, depending on the regulatory approval being sought. So, for example, a hell or high water commitment may be agreed to for Canadian approvals but not for foreign regulatory approvals.

The agreements in the Glencore/Viterra and CNOOC/Nexen transactions had hell or high water types of covenants. CNOOC agreed to a reverse break fee of US$425 million and Glencore to a reverse break fee of C$50 million. In some cases, particularly in multijurisdictional transactions, deal terms may impose different obligations on buyers, depending on the regulatory approval being sought. So, for example, a hell or high water commitment may be agreed to for Canadian approvals but not for foreign regulatory approvals.

Competition Risk Should Not Be Overlooked

For both foreign and domestic investors, competition risk also continues to be an issue that must be managed. This was highlighted by the decision in Commissioner of Competition v. CCS. In that case, the Competition Tribunal ordered the divestiture of an acquired business in connection with a small ($6 million) non-notifiable merger on the theory that the target would have started to compete with the buyer in the future. The case makes upfront assessments of competitive effects more complicated. A merging party acquiring a non-competing business must now consider whether, in the absence of the merger, the target might start to compete with the buyer and whether, in that hypothetical scenario, any resulting impact on competition would be substantial. The case also makes risk assessment more complicated for vendors, which may be involved in post-closing reviews or potentially required to reacquire the business if transactions are unwound, a remedy the Commissioner was seeking in the CCS case.

Some of these risks can be managed in M&A agreements through indemnification provisions or making preapproval a condition of closing, even if not required by law. However, it is clear that, at a minimum, advance consideration of potentially highly complex issues is becoming increasingly critical.

The regulatory uncertainty brought on by the rising incidence of foreign investment in Canada, particularly by SOEs, will inevitably encourage parties to address regulatory risk in pursuing their inbound investments in 2013. While we expect that most foreign investments into Canada will proceed in the normal course, for some investors, prudent management of their investment strategy will help put the odds of clearance on their side.

To discuss these issues, please contact the author(s).

This publication is a general discussion of certain legal and related developments and should not be relied upon as legal advice. If you require legal advice, we would be pleased to discuss the issues in this publication with you, in the context of your particular circumstances.

For permission to republish this or any other publication, contact Janelle Weed.

© 2024 by Torys LLP.

All rights reserved.

Tags